Avalanche — Decision Making in an Uncertain World

I was caught in an avalanche on Sunday, December 2nd, in the Fernie backcountry. There is a lot of uncertainty about what happened, and room for disagreement over my interpretation of events, so let’s start with the facts.

On the morning of the slide, two close friends and I alder-bashed into Cornice Bowl, an exposed, subalpine to alpine bowl under the limestone cliffs of the Three Sisters Peaks. We hiked midway up for our first run. Then one of my friends broke trail above our normal starting point, which involved a steep short climb up a moraine. The other skier elected not to climb the moraine, but I followed on up.

About 20 cm of powder was sitting over an icy crust. I started sliding on the crust, and stomped as hard as I could to hold an edge, but eventually had to take a lower angle up-track. As I was stomping, sliding, stomping and sliding, I thought, “Okay, there is a message here. The snow on top of the crust is unconsolidated. No slab, no propagation of force, hence, it might ooze around a bit, but no avalanche potential from the snow above the crust. At the same time, if my heavy stomping isn’t transmitting below the crust, then the crust is bridging effectively and no avalanche potential from below the crust.” So, despite my frustration and embarrassment, I felt confident in the overall stability of the snowpack. Eventually, I gained the moraine crest. We all de-skinned, and skied high quality snow to the bottom. Smiles and giggles.

We skinned back up, and this time elected to go for the high ridge. After an hour of climbing, my two partners disappeared onto the ridgetop, while I was still 20 meters below the crest. Then, with no warning, no whumpf that I remember, the snow crinkled above me, and collapsed. I rode the size 2.5 avalanche 300 vertical meters, was buried up to my neck, and suffered a broken rib and mild contusion on my quad muscle.

After realizing what happened, one of my partners stayed on the ridge and called Fernie Search and Rescue, while the other raced down to help dig me out. Once extricated, we all skied down to the bottom of the bowl and met the SAR helicopter. Many thanks to those brave people who flew in under marginal conditions to come to my assistance.

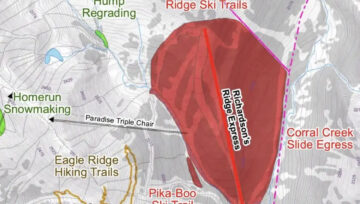

Look at the photo of the slide path. At the point marked with an X, I was carried skiers left into a wide gully. If I had been riding on the portion of the slide that went straight, over the cliff, it would not have been pretty.

So why did three experienced backcountry skiers end up in a crisis? Let’s go back to the beginning.

We started off the season with a little bit of snow, followed by a cold spell. I wrote on powdercanada.com, “the snow depth was 35 cm and weak, unconsolidated, surgery — rotten to the ground.” Then we got a warm storm, with rain at lower elevations and wet snow up high. The wet layer froze, forming a hard crust, with 20 cm of dry powder on top. Avalanche Canada’s forecast for our region recognized that the original weak layer was mostly neutralized and therefore the danger level was ‘Moderate’ in the Alpine and Subalpine and ‘Low’ in the timber. I’ve skied in these conditions thousands of times. But along with this benign forecast, Avalanche Canada advised,

“Start scared! Guides start out on small slopes with no consequences and slowly build up to more committing slopes, but only if there are no signs of instability. Potential signs of instability to watch for are any of the following: recent natural or human-triggered avalanche activity, small rolls releasing under your skis or sled, seeing cutbanks pull out by the side of an access road or trail, whumpfs, (rapid collapses of the snowpack on lower-angled terrain) or cracking of the snow surface. If you do see any of these, the simplest course of action is to stick to lower angled slopes.”

On the day of the slide, we followed Avalanche Canada’s recommendations exactly, starting on a less committing run. When we reached our previous high point, on the second skin up, we were all keen to hike on up to the ridge. Why? What’s the human factor here? Well, we’re mountaineers. Mountaineers like to go up. No deep complexity or technical mumbo jumbo required. And in our defense, coupled with that desire, all of our observations indicated that there were no failure modes. Nothing. Nada. Zero. No hairs standing up on the back of our necks.

As we climbed toward the ridge, into ever more committing terrain, each one of us, independently, made ongoing evaluations, probing with our poles, doing hand shears, listening, watching. When we compared notes after the incident, no one found anything alarming that might have called for a premature retreat. There was powder over a solid crust. Maybe there was a surface hoar layer down there, and maybe not, but the surface snow was soft, exhibiting no slab properties, and the crust gave absolutely no indication of failure.

Despite all of our precautions and observations, just below the top, with fond thoughts of a rest, drink of water, and a fun ski down, disaster struck.

I’ve been involved in tragic slides twice before, but in those two instances, I had observed – and ignored – warning signs that I should have taken seriously. This time, no matter how hard I search my memory, no matter how much I brainstorm with my partners, none of us can recall any warning signs. Nothing. Nada. Zero.

Gord Ohm is a respected of avalanche forecaster who lives in the Elk Valley. I went to his house to ask if he could dissect our decision process and help me pinpoint where we had gone wrong.

We talked for several hours. Gord stressed that while the avalanche probability reported by forecasters on the Avalanche Canada website is regional, each specific avalanche is dependent on the microenvironment exactly at the starting point. Cornice Bowl is a unique microenvironment, requiring its own evaluation. But it’s more complicated than that. Every step you take, you are entering new micro-micro environment. So the snowpack 20 meters below the ridge is different than the snowpack 100 meters below the ridge, which is different than the snowpack on the moraine half way up, and so on. Some little wind swirl, or something, created a critical start zone right there at the ridge. All the information we had accumulated at lower elevations didn’t accurately describe the conditions at the start zone.

The skier who broke trail emailed me: “I did not feel any difference in the last 20 meters from the ridge (where the slide initiated), BUT as we discussed, at that point human nature takes over, and you just want to get over the ridge.“

Gord asks, “Did you, as third in the party, compress the skin track and stomp additional forces onto the unstable interface of the snow and ice? Or, is it possible that your partners, moving around on the ridge, triggered the slide remotely from the top? There is a scientific answer. If you had died, an avalanche technician, dispatched to the scene by the coroner, would probably have figured it out.”

Well, I didn’t die, so they won’t fly an expert up there and give us the scientific answer. And my buddies were too busy rescuing me to study the snow crystals at the start zone with a magnifying glass. So we don’t know precisely what happened. But, because I am a skier, deep in my heart, because as soon as this rib heals, I’m going back out there, I would really like to know what happened. Was it random bad luck (whatever that means) or did I (we) make a mistake that day?” Well, yeah. Duh. I’m the guy with the broken rib, so yeah, there was a mistake. But, I’ll add to that. In my opinion, the failure mode was subtle. We didn’t make an obvious mistake.

And here is the final take-home: On most of our favorite ski runs, there is a safe way up. You have the luxury of evaluating the slope, digging a pit at the start zone, and ski-cutting the start-line, before you drop in. Some places, like Cornice Bowl, are inherently dangerous. When you are hiking up the belly of the beast, you are, by definition, ratcheting up the ante. So it all comes down to the base level risk assessment we make when we get out of bed, cross the street, or choose to venture into the high peaks in winter.

Comments