The Finger of God

If you spend time in the backcountry, you have likely seen the recent New York Times feature Snow Fall, with its detailed analysis of the February 2012 Tunnel Creek avalanche. That story, which went viral in part due to its groundbreaking integration of multimedia, and an earlier Outside piece on the same event (Tunnel Vision ) are both well worth reading for their revealing look at decision making and group dynamics in high risk situations.

I stumbled across the article on Christmas Eve, quickly drawn into the compelling events. But as the story unfolded, I found myself more and more shaken by the eerie similarities between the Tunnel Creek incident and my own ‘near-miss’ in avalanche terrain just a few years earlier.

The lead up to both was identical: heavy snowfall, experienced skiers, and most critically, concerns that went unvoiced. Although our group was smaller (just four of us), the physical terrain and skier placement across the slope bore an uncanny resemblance. Two members of our party remained high on the ridge. One skier had descended partway, and was waiting in a clump of trees. I skied next. If you have read Snow Fall, I was Jim Jack. I was the skier who triggered a slide that ripped across the entire slope, funneling into a steep, rocky gully and running all the way to valley bottom.

And that is where the similarities end. Jim Jack died, probably within seconds. The friends that dug him from the debris pile discovered a pummeled body, folded in half backwards with feet above the head. Cause of death was officially listed as brain trauma, but the medical examiner also noted partially torn aorta, broken neck, broken vertebrae, broken sternum, broken ribs, and internal blunt force injury. Two of Jim Jack’s companions also perished that day.

We all skied away. And to to be fair, our survival was nothing more than fluke. Tunnel Creek highlighted the conclusion of the story that we, and our loved ones, narrowly avoided: the sense of utter helplessness amid powerful moving snow, the disbelief and then despair in the silence afterwards, the frantic 911 calls, the rescue, the survivors, and the lives changed forever.

Perhaps because I felt embarrassed, or perhaps because in no way did I want to appear to be assigning blame, I let our incident slip by quietly and unnoticed at the time. After reading Snow Fall, I now feel compelled to share it, in the hope that its lessons might help other backcountry enthusiasts.

It started, as all adventures do, with the simple, wholesome desire to have some fun.

My good buddy — and expedition partner of fifteen years– suggested we go ski touring. Despite the fact we live in the same small town, busy schedules had prevented us from getting outside together for over a year. To remedy the situation, we picked a day, and marked it in our calendars weeks in advance.

Then, the night before our planned departure, a heavy winter storm blew in. By dinnertime, snow was piling up at over an inch an hour, and for the first time, I began wondering about our plans. Had the commitment been with anyone else, I would have suggested spending the next day at our local ski hill instead of traveling in the backcountry. But there was human history to consider. For years, I’d been the conservative one in our partnership; the one suggesting bailing when things didn’t look or feel right. It had become such a bone of contention that my friend and I began doing less together. This outing was supposed to be a step towards healing that rift. And I knew he’d still be gung-ho. I set my alarm for 5:30 am.

By dawn, a foot of new snow lay on the ground outside my house. There would be more in the high peaks. But neither my friend, nor the two experienced skiers he’d invited to join us, seemed concerned. Lacking the heart for confrontation, I decided, I’d bite my tongue, and bite it all day long if necessary. For once, I’d go with the flow. That mistake nearly killed me.

The road into the mountains — one we knew well — was obliterated beneath a blanket of featureless snow. Just minutes outside town, my friend missed a curve and drove full speed down a farmer’s lane, soft powder billowing over the hood as we drifted to a stop. Even as it happened, I knew it was another warning. We should have turned back. But we didn’t.

After parking the cars, an hour-long snowmobile ride along abandoned logging roads, brought us to the foot of the basin where we planned to ski. Heavy clouds and mist meant we could see nothing. I’d visited the valley before in the summer, but never winter. Now I would have to rely on others for their understanding and judgement of the terrain both above and below us.

Even as we attached skins to our skis and tested beacons, the ominous sound of natural avalanches filtered through the forest. Somewhere, in the cliffs far above, snow was coming down on its own. First one. Then two. Then three. Surely we weren’t going to ski now? “Not a problem,” someone explained. “We can stick to safe trees.”

Skinning upwards, the trail we cut felt protected, weaving thought stands of old growth draped in ‘old man’s beard.’ An hour later, as we reached a high ridge, the trees were thinning. In the mist to our left appeared silhouettes of thicker forest. To our right, blowing snow and cloud obliterated what looked like an open slope. ‘Which way?’ shouted my friend, in the lead. ‘Go right’ came the answer from behind. “Better turns.” I knew it was the wrong call, but said nothing.

We had a quick snack, shared a few sips from a thermos of tea, took off skins, made a plan, and then dropped in. Skiing one at a time, we regrouped after just ten turns in a small clump of wind-blown alpine larch. Then the first skier set out again. Soon his faint call wafted up through the mist, ‘Safe!’ I went next.

Six turns in I dragged a hip in the powder to slough speed, and I suspect that is what broke the hillside free. Suddenly, everything in front of me was moving. As far as I could see, the slope was breaking into blocks the size of washers and driers, tumbling away as puffs of snow rose like smoke. Without even thinking, completely instinctively, I turned away from the chaos. But ahead of me, in this new direction, everything was moving too. Not knowing what to do, I put on the brakes.

Far above, I heard my friend scream, ‘“AVALANCHE!” There was an urgency in his voice I’d never heard before in fifteen years of friendship. My skis ground to a stop. I wasn’t moving? The hillside was silent. From below, a muffled cry: ‘I’m OK.’

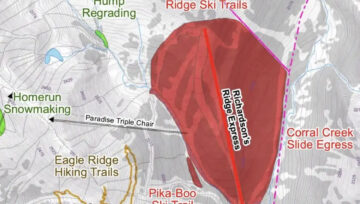

It took a moment to piece together what had happened. A massive fracture had ripped across the slope above; 160 centimetres deep and roughly 100m wide. Miraculously, a single vertical finger of snow — smack in the middle of the avalanche path — had not slid. And that finger extended all the way down from the crown to the point where I now stood. I’ll never know whether it was the hand of god, or micro variations in the terrain, but I was perched atop the only safe island in a swath of total destruction. Had I been skiing just a few metres to either side, I’d have been swept away.

But what of the skier below?

Leaping off the ‘snow finger’, my skis landed on a rock hard snow surface (which the avalanche slid upon.) Side-slipping as fast as I could, I followed the yells until I spotted him, jammed between two pine trees, buried up to his neck.

“I always stop on the uphill side of trees,” he smiled, still unshaken. It was a decision that probably saved him. By the time I’d dug him out, the other two had joined us.

The slide I triggered ran over 800 metres to the valley bottom. We followed its path though the old growth stands where we’d skinned earlier. Far overhead, beyond the reach of our extended poles, was a “high-tide” mark of refuse (branches, twigs, ice) showing the depth of snow that ran through these stands. Below, the slide funneled into a rocky gully, tumbling downwards and eventually spewing across flats below.

The burning question is how could I have been such a fool? Why did I remain silent in the face of so many alarms and obvious warnings?

I am an extremely conservative decision maker, with many avalanche courses under my belt and twenty plus years experience traveling in the backcountry. The fault for silence is all mine; my companions bear no blame.

In hindsight, of course, the events appear ridiculous. Almost unfathomable. But human dynamics, personal histories, the perception of pecking-orders, the unspoken hierarchy of experience, the desire not to disappoint others, even those we barely know – these are powerful forces. Anyone who spends time in the backcountry will recognize these influences, and I suspect will have wrestled with them at some point.

In the days and weeks following the “near miss”, as I tried to make sense of the events, and understand how to avoid similar situations in the future, three themes emerged. They by no means encapsulate all the human factors that can influence backcountry decision making, but I think they are a good starting place. I made an oath to myself to follow these as best I possibly could. They are unquestionably what I’ll impress on my boys if they decide to explore the backcountry in the future. And I share them now in the hope they might benefit you, or the ones you love:

Always speak up. If you have reservations about snow conditions or route decisions, speak without reservation. Speak even if you don’t know why you are worried. Speak if it is just a feeling in your gut. Ignore any concerns you might harbour about the judgements of others. Speak up because it is the only way you will learn. Speak up because you care about the lives of the people you are with. This sounds easy, but anyone who has spent time out there knows it can be challenging at times. At least ten of the extremely experienced skiers standing atop Tunnel Creek harboured concerns. Not one said a word, thinking someone else would chime in if it was necessary. Don’t wait for others. Speak up.

Do not defer to experience and local knowledge, especially when it is pushing you towards a decision that feels uncomfortable Your opinion and judgement matter as well. Experience and local knowledge can be powerful forces in groups; but they are not always right. Other factors may be at play — including overconfidence, overfamiliarity, and even the false sense of security that comes from surviving previous bad decisions. Trust your inner voice. Conversely, if you ever find experience and local knowledge suggesting you be more conservative with your decision making, listen up.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly gravitate towards partners who are more cautious than you. Not because someone is “right”, and someone else is “wrong”; risk assessment and acceptance is highly personal. But, in my opinion, it is far better to find yourself mildly disappointed at the end of the day (when your group did not accomplish everything you’d hoped) than to find yourself dragged into situations you don’t like. The best thing I ever did was align myself with a handful of skiers who are just as happy to spend a day poking through valley bottom forests as they are to summit a big peak. Any turns we happen to get are an added bonus to the main joy of simply exploring the outdoors.

Staying safe in avalanche terrain has always been an odd mix of science and zen, of collecting facts while simultaneously listening to instinct. It is a game of constant observation in the search for ultimately unattainable answers. No one can tell you, with absolute certainty, whether a given slope on a given day is safe or not. You might ski a run where nothing releases, but still have made a mistake. If you walk away from a slope, you’ll never know if you were being wise, or unduly conservative. So instead, the best we can do is stack the odds heavily in our favour.

A solid understanding of snow science, weather patterns, pack history and avalanche dynamics is the starting point. Carrying all the requisite safety gear, and knowing how to use it, tips the balance further in your favour. After all that, don’t make the mistake I did and allow the unspoken, universal human issues we all wrestle with to pull even one chip from your stack.

Written and photography by Bruce Kirkby

Previously published and comments at blog.mec.ca

Comments