Say No To Crack!

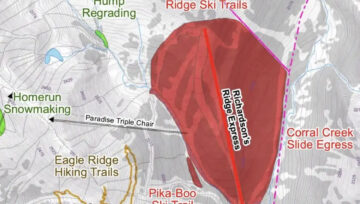

Mount Fernie forms a prominent glide crack on its south face in clear view of town every winter. The specific area is called the Moccasin due to its shape and distinctive grassy summer surface. This year the glide crack has formed earlier and larger that most seasons and we’re questioning when it will avalanche.

Jennifer Coulter, Avalanche Canada’s field technician, commented, “Glide releases in January are perhaps not the norm, but they do happen! This is a post from January 2019, from another Mount Fernie glide performer. Temps were not warm when it happened either, it had been around -5 with no big weather inputs the previous days.”

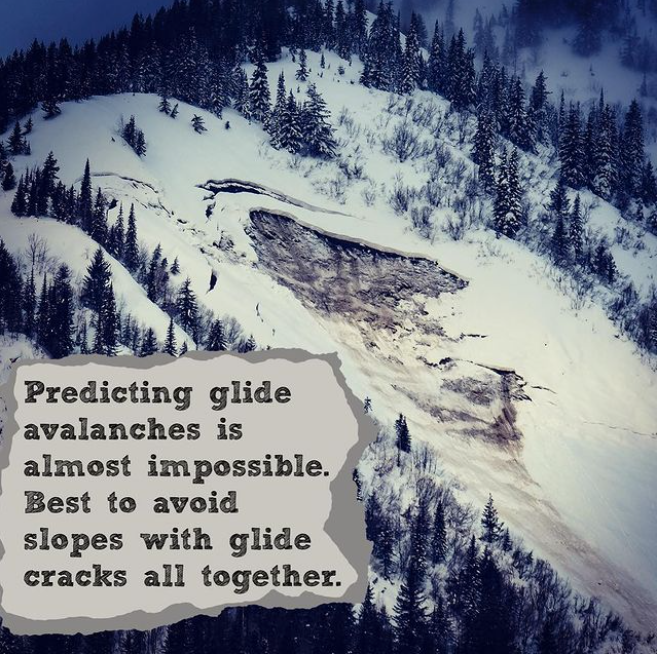

A glide Avalanche release is challenging to predict. Glide cracks display slope instability and the potential to avalanche so it’s best to stay off the crack!

About Glide Cracks

Release of the entire snow cover as a result of gliding over the ground. Glide avalanches can be composed of wet, moist, or almost entirely dry snow. They typically occur in very specific paths, where the slope is steep enough and the ground surface is relatively smooth. The are often proceeded by full depth cracks (glide cracks), though the time between the appearance of a crack and an avalanche can vary between seconds and months. Glide avalanches are unlikely to be triggered by a person, are nearly impossible to forecast, and thus pose a hazard that is extremely difficult to manage.

Predicting the release of Glide Avalanches is very challenging. Because Glide Avalanches only occur on very specific slopes, safe travel relies on identifying and avoiding those slopes. Glide cracks are a significant indicator, as are recent Glide Avalanches.

Free water collects along the ground surface and lubricates the snowpack. The water can come from snowmelt or rainfall. As the water pools and reduces the friction holding the snowpack to the underlying surface. Wet snow is more viscous than dry snow, so a wet slab deforms and “flows” downhill easier. Glide is usually a slow process occurring over several days or weeks, but occasionally happens much faster. If the gliding snowpack breaks free of the surrounding snow it can avalanche. Glide cracks may open up in the snowpack, but do not necessarily indicate an avalanche is imminent.

Glide Avalanches occur on smooth slopes. Grassy slopes, rock faces, and glacial ice or firn are common surfaces. The free water can spread evenly, and it is easy for the water to drown surface roughness. Very rough surfaces tend to channel water, rather than allowing it to spread out, and have very high friction.

Glide cracks often form where the ground surface changes from rough to smooth, and on convex rolls with a smooth surface. Glide Avalanches tend to happen on specific slopes.

The Mocassin Glide Avalanche on Mount Fernie brakes to the ground on a steep, smooth and grassy slope.

Glide Avalanches require free water in the snowpack. In a continental snowpack, most free water comes from melting in the spring. Glide Avalanches tend to be late spring events in Colorado.

Glide Avalanche release is challenging to predict. Surface conditions are not a good indicator, because it can take hours or days for free water to run through the snowpack and pool on the ground. Several days of warm temperatures can make glide avalanches more likely, but the avalanches sometimes release after the temperatures cool, but free water continues to run through the snowpack.

Glide cracks are an indication that glide avalanches are possible. The cracks point to slopes with sufficient smoothness. Because the gliding occurs at the ground surface, the rate is hard to observe. There is not a direct correlation between weather events and Glide Avalanches, so those factors are not useful predictors.

Predicting the release of Glide Avalanches is very challenging. Because Glide Avalanches only occur on very specific slopes, safe travel relies on identifying and avoiding those slopes. Glide cracks are a significant indicator, as are recent Glide Avalanches.

Be safe out there!

Comments