Overconfident in the backcountry?

When I lived in the mountains of Utah, I used to ski in the backcountry often. This is not resort skiing, and there is no patrol checking for avalanche risk, so assessing that risk becomes your own responsibility. It is an imprecise science, and there is always a chance you’ll get it wrong.

When I lived in the mountains of Utah, I used to ski in the backcountry often. This is not resort skiing, and there is no patrol checking for avalanche risk, so assessing that risk becomes your own responsibility. It is an imprecise science, and there is always a chance you’ll get it wrong.

But the more my friends and I skied, the more certain we were of our ability to get it right. Here’s what happened over and over again:

1. We’d get to a slope, assess the risk and decide to ski.

2. We’d get to the bottom safe and sound.

3. We’d pat ourselves on the back for being so good at judging avalanche danger.

4. Repeat.

You don’t have to know much about backcountry skiing to imagine how dangerous a feedback loop like this can be. We were attributing a positive outcome to our skill, when it just as likely could have been (and probably was) luck.

Skiing isn’t the only place I’ve seen this kind of feedback loop. It also shows up in investing. Here’s how it tends to play out:

1. John Doe reads one whole book about Warren Buffett and decides he is an amazing investor.

2. After that extensive round of research, he buys a handful of stocks on a hot tip from his golfing buddy.

3. The stocks perform well over a short period of time.

4. John pats himself on the back for such skillful investing behavior.

5. Repeat.

Remember what I said about assessing avalanche danger? It’s an imprecise science, and there’s always a chance you’ll get it wrong. Guess what? That goes for investing, too.

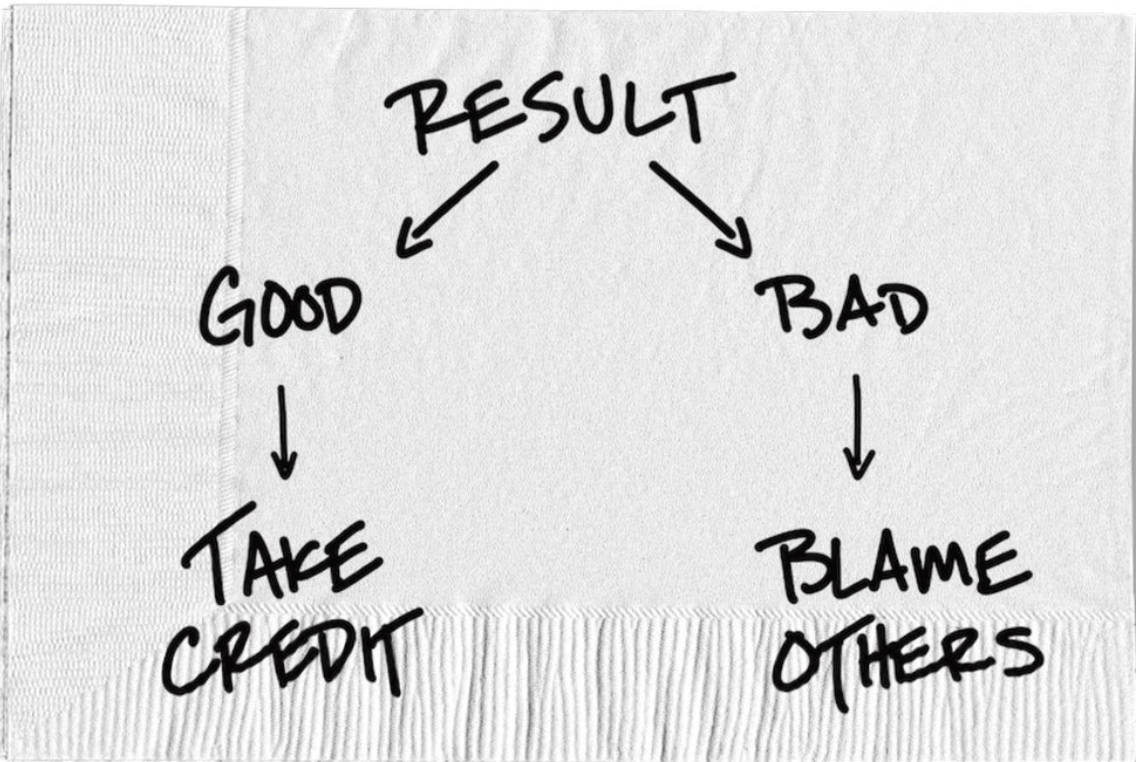

When we’re betting money on the stock market, it’s important to remind ourselves of something called the self-serving bias, where we take credit when things go well and cast blame elsewhere when they don’t.

One of the reasons these biases are so scary is that expertise — the kind professionals are often so certain they have — doesn’t solve the problem. In fact, it might even make it worse.

Just look at Daniel Kahneman. The guy won a Nobel Prize in economics for research into these exact biases. You know how he responded when an interviewer asked if he was less likely to make poor decisions because of his work? “Not at all,” he said. “And furthermore, I have to confess, I’m also very overconfident. Even that I haven’t learned. It’s hard to get rid of those things.”

So are my ski buddies even cognizant of this bias? Some of them told me that they were keenly aware of how many people it has killed in the adventure sports world. Others were in denial, thinking they knew better.

But my friend Eric’s response was the one that stuck with me the most. He probably knows our ridgeline better than anyone. Yet here was his email:

“I’ve dodged my share of bullets through sheer luck or my guardian angel. I skied right down the middle of a face called West Monitor this year on a day I shouldn’t have. Someone had already skied it, and it hadn’t avalanched, so I followed. I felt like I was going to die the whole way down.”

A few hours later, another group was tempted to try the same area. Eric watched as the first skier tested the slope. An avalanche broke out and ran all the way to the bottom, taking out the ski tracks that Eric’s group had made.

He continued: “It’s amazing that I can be this old and experienced and still make an incredibly bad decision. It is so easy to avoid the work of determining risk based on today’s conditions and just pretend that it’s fine because it’s always been fine.”

Eric is no daredevil. You don’t make it to your late 50s as a backcountry skier if you aren’t careful. But even he is not immune to the self-serving bias.

So if my friend Eric isn’t immune, and if Daniel “Nobel” Kahneman isn’t immune, don’t you think there’s a chance you might not be, either?

By Carl Richards, previously published in the NYTIMES

Comments