“Buried” by Ken Wylie

As with most avalanche stories reported in traditional media, not all of the facts are correct. The Durrand Glacier avalanche story is different—the autocratic behaviour and arrogance of Rudi Beglinger is very accurate. The suggestion that his clients are experienced backcountry skiers is a stretch. Rudi’s clients are keen skiers who are looking for leadership and adventure in the backcountry, they are not decision makers or experienced, rather followers who entrust their guide. Some have never backcountry skied prior to Durrand, others like Craig Kelly were very experienced. For Ken Wylie, a mountain guide, he too was a follower–waiting for the next command from his boss, Rudi the autocrat. Ken’s book “Buried” will help those interested understand what really happened and reopen the question of why Rudi never accepted responsibility for his mistake. Editor

Ken Wylie had made up his mind. On Friday, he would march up to the Durrand Glacier Chalet and quit.

He was not interested in working for Selkirk Mountain Experience — a rock climbing, hiking and backcountry ski operation headquartered at the chalet — because he wasn’t interested in working with owner and lead guide Ruedi Beglinger.

True enough, Mr. Beglinger was a legend, a mountain Mozart. And watching him take guests around the backcountry to ski in the Selkirk Mountains, 35 kilometres northeast of Revelstoke, B.C., was a thing of beauty.

But it was also Ruedi’s show, Ruedi’s rules — and Ruedi’s temper ruled. He addressed Mr. Wylie, a 38-year-old with 20 years of experience, as a rookie, barking orders, cussing over the radios, bawling him out for babying the guests.

So, shaking himself out of bed at 4:30 a.m. on Monday, Jan. 20, 2003, Mr. Wylie slipped on an orange wind-shirt and striped toque and told himself to just stick it out until Friday — then hand in his notice.

But sticking it out would be tougher than Mr. Wylie could ever imagine. Because on that Monday, he and his boss took 19 skiers into the mountains, where an avalanche struck. Seven people were killed.

The event deeply shook Canada’s backcountry community — challenging the culture of guiding — and sparked an international press frenzy. The guilt also shattered Mr. Wylie’s life.

In a controversial new book, Buried, Mr. Wylie speaks out for the first time about what happened on the mountain — and why he didn’t stop skiers from going into territory he knew was risky.

“I really needed to be the best me that day, and I was the worst me,” Mr. Wylie says.

Guide as god

“What’s the difference between God and a mountain guide?”

“God doesn’t think he’s a mountain guide.”

Ruedi Beglinger used to tell that joke, before Jan. 20, 2003. In some ways, he had earned the punchline.

Mr. Beglinger was born and trained in the Swiss mountains and had a perfect safety record for 18 winters before the avalanche. He didn’t just work in the mountains, though, he lived in the Selkirks, up high, at 1,941-metres, in a helicopter-access only chalet with a wood stove and 360-degree views that he’d built for his family.

To ski with the ultimate guide in a landscape ringed with jagged peaks and arguably the best snow and ski conditions in Canada, guests would pay up to $1,500 a week. All of them were experienced backcountry skiers who knew the risks. Avalanches were simply part of the environment. Thirteen people were killed in nine separate slides in the Alberta and British Columbia backcountry in 2002 alone.

But men like Mr. Beglinger – 48 at the time, with intense blue eyes and a suitably weather-beaten face – were also considered pioneers of Western Canada’s backcountry. Breaking trails. Reading terrain. Pushing people into places they would never push themselves. Trust wasn’t even a question.

Hans Gmoser, out in Canmore, Alta., and Sydney Feuz, over in Golden, B.C. – these were the guides who had opened up new winter playgrounds to the masses, because they were considered the best, the wisest, disaster-proof masters of a perilous environment.

“There are old guides and there are bold guides, but there are no old bold guides,” Theo Meiners, another legendary guide in Alaska, used to quip.

A perfect day

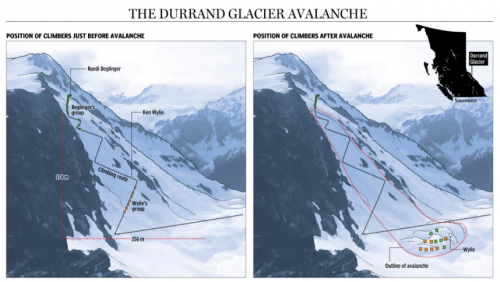

And on that January morning in 2003, the skiers with Mr. Beglinger and Mr. Wylie were stoked. The temperature was -7 degrees, the winds light. By 8 a.m., they split into one group led by Mr. Beglinger, another by Mr. Wylie and left the lodge to put on their climbing skins.

Ken WylieKen Wylie is speaking out for the first time about what happened on La Traviata West Couloir in 2003 — and why he didn’t stop skiers from going into territory he knew was risky.

Their goal was to ski Fronalp Peak, about 2,500 metres up the mountain. But bluer skies beckoned over La Traviata West Couloir, a 180-metre slope at a slightly lower elevation, bordered by cliffs to the west and steep terrain to the east.

Mr. Beglinger radioed his assistant, informing him plans had changed. The groups would ski La Traviata together.

Mr. Wylie didn’t like what he saw above: a terrain studded with rocks — hazards for skiers, which can also conduct cold into the snow and produce weak points.

And two groups, one below the other, ascending a 35-degree slope in an area rated as an avalanche risk was a no-no. The slope itself ended in a terminal moraine — a rock wall, in effect — that could act as a terrain trap, a snowy tomb for any skiers swept into it by a potential slide.

“I was extremely conflicted, standing at the edge of that slope,” he says. “I had always considered myself as this overtly courageous person, because of the things I had done in the mountains, but in a hazardous environment, you need to have the social courage to speak up.”

I had always considered myself as this overtly courageous person, because of the things I had done in the mountains, but in a hazardous environment, you need to have the social courage to speak up — Ken Wylie

Mr. Wylie said nothing. Instead, looking up at his boss’s group and seeing them making safe passage, he checked the snow for stability (it was solid), rationalized away the risk (ignoring his intuition) and started to climb.

One by one, the group followed.

An avalanche is preceded by a percussive “whumpf,” a rattle-your-bones warning shot indicating that billions and billions of snow grains are breaking apart.

A pause follows, a tipping point between an avalanche that slides, and one that doesn’t. In that hanging moment on La Traviata, Mr. Wylie whispered to himself: “Maybe we will get lucky here.”

Then a voice from above shouted “avalanche” and the world came unhinged.

Mr. Wylie could see the skiers below him being bowled over by a wall of snow, a tangle of arms and legs and equipment. Then he too was knocked on his side. He immediately kicked off his skis and tossed his poles, freeing his hands to fend off the rushing snow.

“I was able to stay on the surface — I wasn’t tumbled into the avalanche,” he says. “Later I would think that this was because of my training. But now I realize it was pure luck.”

It was luck, he says, that he was buried facing downhill, and left with an air pocket.

“I was so exhausted of battling, of battling everything that had been going on inside me that day — and that was probably a gift from above, because I gave into the exhaustion. I didn’t panic. I put my head down and passed out.”

Thirteen of the skiers were buried, including John Seibert, a 54-year-old geophysicist from Wasilla, Alaska, and veteran of eight previous trips with Selkirk Mountain Experience.

He was the third skier in Mr. Wylie’s group and remembers “butterflying” his “big long arms” in a maniacal backstroke to stay on top of the snow. When the avalanche exhausted itself he was imprisoned up to his neck, with his left hand sticking out.

“Everything stopped moving and it was silent,” he says. “I couldn’t even wiggle.”

Charles Bieler, a guest from Mr. Beglinger’s group, skied down and asked if he could breath. Mr. Seibert answered yes, and his would-be rescuer skied off, saying there were a lot of people to dig out and that they would get to him as soon as they could.

Someone eventually did, digging into snow as solid as the frozen drifts left at the side of the road by a city plow, and handing him a shovel to finish the job.

“I stood up and could see the extent of the avalanche,” says Mr. Seibert. “When we started out, it was this nice pristine slope, but all I could see was disturbed snow and a whole lot of experienced people, digging, doing the best they could.”

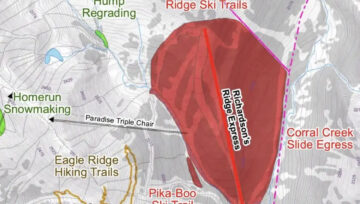

The avalanche struck in three successive waves. The first ripped loose from above, at approximately 2,450 metres. A second, smaller slide followed. Then came the deadly third hit, some 65 metres in width and as deep as 260 centimetres in parts; it spilled down the groups’ ascent route and ran downhill for 350 metres.

One analyst later estimated that the avalanche debris area contained 47,000 cubic metres of rock-solid snow.

As skiers were freed, they searched for others who might still be buried. But their heroic efforts ended repeatedly in despair: Jean Luc Schwendener, a chef from Canmore, dead; Vern Lunsford, an aerospace engineer from Colorado, dead; Dennis Yates, a ski instructor from Los Angeles, dead; Kathy Kessler, a realtor from northern California, dead; Naomi Heffler, a canoe guide and engineering grad fresh out of the University of Calgary, dead; Dave Finnerty, an SME apprentice from New Westminster, B.C., dead.

Craig Kelly, a four-time world champion snowboarder from Mount Vernon, Wash., was buried almost three metres deep.

But Mr. Wylie’s run of good luck hadn’t exhausted itself. Mr. Bieler picked up a signal from his avalanche beacon, 1.9 metres beneath the snow.

Now a wine broker in New York, Mr. Bieler had been in the lead group that morning and recalls being “overcome with fear that something wasn’t right” about halfway up La Traviata. So he sprinted to the top — passing three people on the ascent, all of whom perished.

It wasn’t until nearly 30 minutes after the avalanche that he found Mr. Wylie. John Seibert joined in the dig to free him.

“I remember Ken kind of shaking his head and staring up at me and saying, ‘John,’” Mr. Seibert says.

Mr. Beglinger had radioed for help immediately after the avalanche struck. Several helicopters had descended on the area to assist in the rescue. The lead guide eventually climbed into one of them, telling the pilot to fly up close to the mountain face where the slide broke loose. Ruedi Beglinger wanted answers.

But a few days later he would tell Ted Kerasote from Outside Magazine that he had no misgivings about his decision to ascend La Traviata.

There was “absolutely no doubt about it — can I go, can I not go,” he said. “It was a clean decision. The snow was super-strong, super-positive. Fantastic.”

The aftermath

The media didn’t necessarily see it that way.

CNN came to Revelstoke. The Today Show called. What they wanted to know: Was someone to blame?

Ken Wylie, freezing cold and unsteady on his feet, had been flown to the hospital before the international press arrived. Which left Mr. Beglinger to face the media alone.

“He experienced things on that day that I wouldn’t wish on anybody,” says Mr. Wylie. “He took the brunt of it.”

The B.C. Coroner’s office was also brought in to conduct an inquiry into the tragedy, which included an extensive analysis by Larry Stanier, an avalanche expert now in Canmore, Alta.

He acknowledges that there is “always a degree of risk in the backcountry,” but says “there was no reason why [Mr. Beglinger’s group] couldn’t have been out there.”

The Coroner ruled that the seven deaths were “accidental” — caused by asphyxiation from being buried in the snow.

“Ski touring is an inherently dangerous sport,” Charles H. Purse, the Coroner for Revelstoke, wrote in his final report. “People who ski at this level are aware of the risk.”

Mr. Seibert agrees. Talking between sips of cappuccino from his Alaska home, he says, “Any time that many people get killed, somebody messed up.” He says skiers like him are aware of the risks they face.

Indeed. None of Mr. Beglinger’s other guests spoke up that day either. “I added it up, and there was 300 years’ worth of ski mountaineering experience on the mountain that day which, I think, begs the question: Why didn’t someone say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, why are we all on this slope?’”

It was an Avalanche 101, bonehead mistake, and I don’t fault Ruedi for that, but what I do fault him for is not being accountable for it — Dick Penniman

But the Coroner’s report wasn’t good enough for Kathy Kessler’s family. She had trained specifically for the trip, despite decades of experience in the backcountry. Ms. Kessler’s family commissioned a report of their own, prepared by Frank Baumann, an engineer in Squamish, B.C.

Mr. Baumann, since deceased, examined weather and wind patterns in the months leading up to the avalanche, the angle and underlying make-up of the slope, the “terrain trap” Mr. Wylie had noted and the lead guide’s decision-making process.

He concluded that, “by taking his entire party up the La Traviata couloir at the same time, the guide was unnecessarily exposing his group to a higher avalanche risk, and not following generally accepted safety procedures.”

Dick Penniman, an expert who taught Kathy Kessler avalanche safety at Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno, Nevada, also did his own analysis, presenting his findings a year later at the International Snow Science Workshop in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

“It was pretty clear what happened,” he says. “It was an Avalanche 101, bonehead mistake, and I don’t fault Ruedi for that, but what I do fault him for is not being accountable for it.”

Then, just 12 days after the slide at La Traviata, it happened again. Seven teenagers on a high school ski trip to Glacier National Park were killed in an avalanche in Rogers Pass.

None of that has spooked the thrill seekers. Although no exact count exists, the number of people accessing the backcountry in B.C. and Alberta — on skis, as well as snowmobiles and snowshoes — has boomed in the last decade.

What has changed is the culture of the backcountry.

Joe Obad, the executive director of the Canadian Avalanche Association in Revelstoke, calls the two avalanches in 2003 “seismic events.”

If anything good came out of that accident, maybe it is how it changed the mindset among the guiding community — John Seibert

“They changed the way risk was communicated to clients — whether it is students on a trip or professional guides with their clients — and it changed the way professionals dialogue with each other.”

In other words, no more blind trust — and no more silence, from assistant guides or skiers themselves, when things look risky on a mountain.

John Seibert has returned to Canada almost every winter, often twice, since the tragedy. He says he doesn’t blame either guide on La Traviata, but that he has seen a positive shift in the way guides and their guests operate.

“Back then there was a guide as god mentality,” he says. “It is a much more collaborative discussion now … If anything good came out of that accident, maybe it is how it changed the mindset among the guiding community.”

Mr. Beglinger is still living in the Selkirks, still guiding trips and pushing skiers into high-risk areas. His bookings are always full. His reputation recovered.

But according to Mr. Wylie, his old boss now skis in smaller groups, and provides guests with avalanche flotation devices. Things have changed at SME. In a documentary about him called A Life Ascending, Mr. Beglinger tells the filmmaker, “no matter how much you know, you can not make the mountains safe.”

Mr. Wylie had a rougher time recovering from the tragedy. His marriage fell apart. He briefly took a desk job with the Canadian Avalanche Association. He did some backcountry ski guiding, but found it incredibly “stressful.”

We are all dealing with this, and there is never a day goes by when you don’t think about it — Nicoline Beglinger

And when the accident came up in conversation, he says, it was easy for him to project responsibility onto Mr. Beglinger. La Traviata was his call. Ken Wylie was just the assistant.

But something was missing from that explanation. He still felt great guilt and doubt. Over time, even his physical state was affected: his shoulder locked up, his back gave out.

So four years ago, Mr. Wylie decided he needed to come clean, with himself and with others. He would write a book about what happened and his part in it.

Who is responsible?

Mr. Wylie also wanted to acknowledge the mistakes he’d made on that mountain to the victims of the avalanche. So he wrote to the family members of those who died.

One of them was Brian Kelly, whose older brother Craig, a snowboard champ, was killed at La Traviata.

“There is not a day that goes by that I don’t think about him,” he says.

Two years ago, when he received a message from Mr. Wylie asking him to meet, he agreed and invited him to his home in Bellingham, Wash., where he lives with his wife and four sons (including one named Craig).

He still remembers Mr. Wylie’s guilt.

“‘I could have radioed Ruedi and said, ‘We are going to sit tight.’ But he didn’t,” he told Mr. Kelly. “He holds himself more responsible for what happened than I do, to be honest.”

And none of it really matters, “this idea of who is responsible,” says Mr. Kelly, “because in the end we lost a lot of great people, and my brother was just one of many.”

Mr. Wylie met with some of the other victims’ families. They were supportive. They didn’t judge. Only one among the seven never responded to his letters.

When Mr. Wylie was finished writing an early draft of his book about the avalanche, he sent a copy to Mr. Beglinger.

“His response was to ask me not to write it,” Mr. Wylie says.

Mr. Beglinger was guiding in Europe and did not respond to a request for comment. But his wife Nicoline answered the phone at the SME office on a recent afternoon.

“We are all dealing with this, and there is never a day goes by when you don’t think about it,” she said, unflinchingly polite, “and if Ken needs to deal with it in this way, that is his right. It is unfortunate that he needs to take Ruedi through the ringer while he is at it, but that is his right to do.”

Mr. Wylie says he continued with the book despite Mr. Beglinger’s concerns because it was the only way he could “find some semblance of peace in all this, by taking responsibility for my own actions.”

Mr. Wylie has remarried and now makes his home in Blacksburg, Va., but he says he and his wife are talking about moving back to Western Canada. He’s also changed his thinking about the backcountry: The mountains used to be something to conquer; now, he sees them as a place to heal.

Last summer, he led a group of Afghanistan war veterans on a trek to the summit of Mount Joffre, in Alberta’s Peter Lougheed Provincial Park. “It’s about letting it all out, and really learning how to talk to one another,” he says. “The mountains are a great tool for that.”

And the boss who made him want to quit just three weeks into his mountain job? He says he is amazed Mr. Beglinger is “out there, every day in the winter, guiding and doing his thing, and doing it with such passion.”

“He is making sense of it in his own way. That is all someone can do.”

By Joe O’Connor

Source: nationalpost.com

Comments