La Niña Watch

Since the demise of the big 2015-16 El Niño in April, the tropical Pacific has been loitering around in neutral… and now forecasters think it’s likely to stay that way through the winter. For now, we’re taking down the La Niña Watch, since it no longer looks favorable for La Niña conditions to develop within the next six months.

What happened?

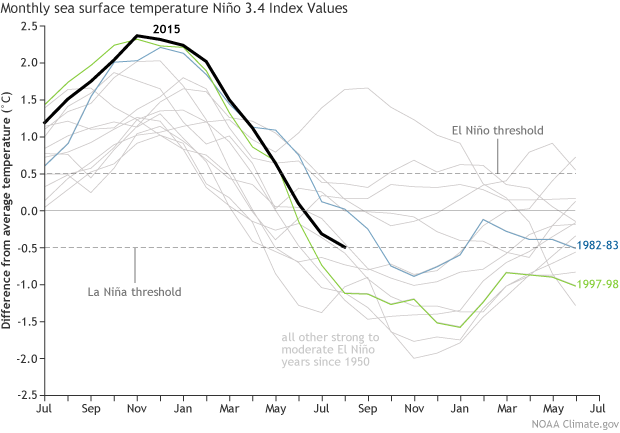

Over the last few months, sea surface temperature anomalies (the departure from the long-term average) in the Niño3.4 region have become more negative, which was expected. Currently, the sea surface temperature in the Nino3.4 region is about -0.5° below the long-term average, according to the ERSSTv4 data.

Monthly sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region of the tropical Pacific compared to the long-term average for all moderate-to-strong El Niño years since 1950, showing how 2015/16 (black line) compares to other events. Climate.gov graph based on ERSSTv4 temperature data.

Monthly sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region of the tropical Pacific compared to the long-term average for all moderate-to-strong El Niño years since 1950, showing how 2015/16 (black line) compares to other events. Climate.gov graph based on ERSSTv4 temperature data.

This is the La Niña threshold! However, the second step of the La Niña conditions decision process is “do you think the SST will stay below the threshold for the next several overlapping seasons?” For now, the answer to this question is “no.”

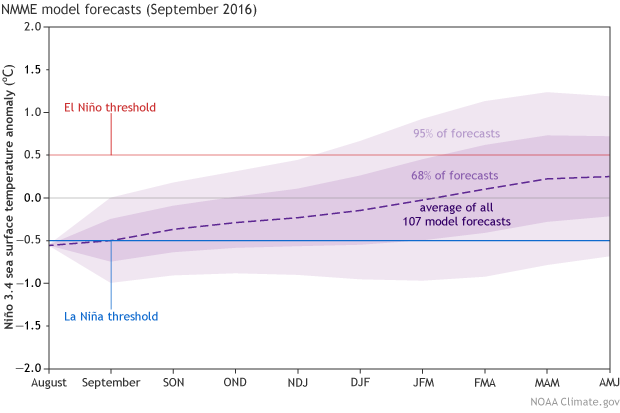

In fact, the dynamical climate models are predicting that this month’s Niño3.4 index will be the low point, and sea surface temperatures will recover to near average over the next few months. There is still a range of forecasts, but all eight of the North American Multi-Model Ensemble models expect the negative anomalies to weaken toward zero.

Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index, from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). Darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. NOAA Climate.gov image from CPC data.

Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index, from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). Darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. NOAA Climate.gov image from CPC data.

What didn’t happen?

Here at the ENSO Blog, we talk a lot about the response of the atmosphere to the change in sea surface temperatures. That’s because it’s critical—you can’t have ENSO without the Southern Oscillation. Just like El Niño, La Niña requires an atmospheric response, and it just hasn’t happened over this summer.

The La Niña response is a stronger Walker Circulation. Even more than usual, cooler air sinks toward the surface over the cooler-than-average waters of the central and eastern Pacific. Meanwhile, the perpetually warm waters near Indonesia warm further, and the overlying air becomes even more warm and buoyant than usual, leading to more vigorous convection (rising air).

These opposing areas of vigorous rising and sinking air amp up the normal circulation across the tropical Pacific: at the surface, stronger-than-average winds blowing east to west, and high up in the atmosphere, corresponding stronger-than-average winds blowing west to east. More rain falls over Indonesia, and less falls over the Central Pacific.

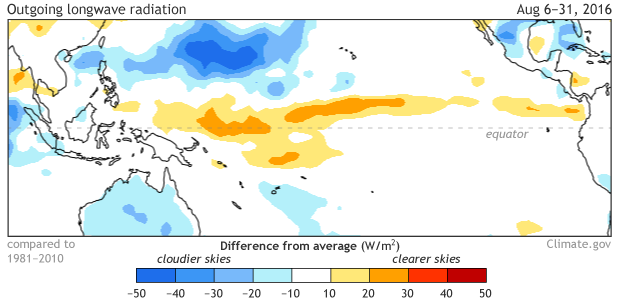

So far, there have only been some very weak indications of this intensification, like a small area of stronger-than-average upper level winds over a localized region of the central Pacific. Also, some extra rain over western Indonesia, and a narrow, but weak, strip of drier-than-average conditions over the cooler waters of the central Pacific.

Blocking of outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) during August 2016. Blue shading shows areas where more clouds than average were present, indicated by greater-than-average absorption of surface OLR (less OLR exiting the top of the atmosphere). Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

Blocking of outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) during August 2016. Blue shading shows areas where more clouds than average were present, indicated by greater-than-average absorption of surface OLR (less OLR exiting the top of the atmosphere). Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

But what needs to happen to really get La Niña conditions underway is for those stronger-than-average winds to blow across the surface of the equatorial Pacific, cooling the surface and helping to keep warm waters piled up in the far western Pacific. We’ve seen some weak bursts of this activity over the past few months, but nothing has settled in for the long haul.

Without this atmospheric feedback, the large area of cooler subsurface waters that we saw back in the late spring has decreased substantially. Yes, the surface has cooled, but there’s not much cool subsurface water left to extend or intensify the conditions. For fun, have a look at the subsurface during August of 1983, 1998—other years following a strong El Niño—and 2016.

What’s going to happen?

It’s certainly not impossible that La Niña could still develop; forecasters are putting the chances for La Niña somewhere around 40% through the early winter. And, while a strong La Niña developed immediately after the 1997/98 El Niño, there was nearly a year of slightly-below-average temperatures following the 1982/83 El Niño before a moderate La Niña eventually developed in October of 1984, further evidence that there are many pathways that the climate system can follow after a large El Niño event.

For now, though, most signs are pointing toward a stronger chance of remaining in neutral conditions for the time being. Between the model consensus and the current lack of atmospheric response, forecasters put the odds of staying ENSO-Neutral at 55-60%. Of course, we’ll continue to keep you posted on all the happenings (and non-happenings) in the tropical Pacific.

Source: September 2016 ENSO update

Author: Emily Becker

Comments