Tropical Pacific now at El Niño levels

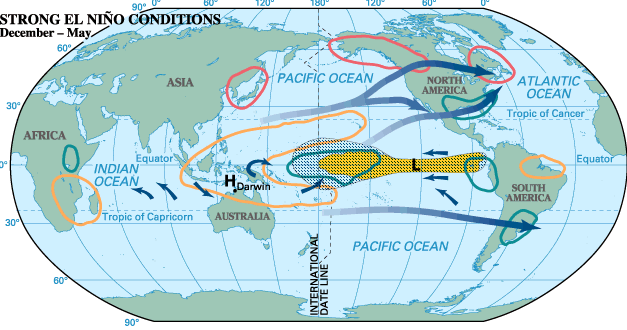

Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology’s latest update on the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) today confirms El Niño thresholds have been reached in the tropical Pacific for the first time since March 2010.

Assistant Director for Climate Information Services, Mr Neil Plummer, said El Niño is often associated with below average rainfall across eastern Australia in the second half of the year, and warmer than average daytime temperatures over the southern half of the country.

“The onset of El Niño in Australia in 2015 is a little earlier than usual. Typically El Niño events commence between June and November,” Mr Plummer said.

“Prolonged El Niño-like conditions have meant that some areas are more vulnerable to the impact of warmer temperatures and drier conditions.

“The failed northern wet season in 2012–13, compounded by poor wet seasons in 2013-14 and 2014-15, have contributed to drought in parts of inland Queensland and northern New South Wales,” he said.

Mr Plummer noted that while the El Niño is forecast to strengthen during winter, the strength of an El Niño does not necessarily correspond with its impact on Australian rainfall. Australia experienced widespread drought during a weak El Niño in 2006–07, while stronger events such as the El Niño event in 1997–98 had only a modest impact on Australian rainfall.

He says winter won’t necessary be cancelled, but we probably won’t “have bouts of subfreezing temperatures that we did last year.”

As in Atlantic Canada, El Nino won’t necessarily affect the amount of precipitation so much as the type of precipitation.

“In Toronto, we almost get as much rain as we do snow in the wintertime,” says Phillips. With El Nino, Ontarians and Quebecers may have to break out the rain boots more often than not.

Prairies

Phillips says that the Prairie provinces tend to be a little drier during an El Nino, but because they see so little precipitation anyway, it tends not to be a factor.

“They’re not going to lose their crop in an El Nino,” he says. “Winter is a dry season anyway.”

One potential outcome is that there might be less flooding come the springtime, welcome news to those still reeling from the 2013 floods.

A mild winter in 2010 left the Vancouver Olympics short of snow.

Because it’s closest to the oceans where El Nino develops, British Columbia would feel the effects the most.

Phillips adds that warm winds blowing from the west could also effectively push cold air back up north — meaning less snow and higher temperatures for the region. “There’s a number of things that roll together here,” he says.

Less snow and rain could be a problem for the province’s economy, however, especially for tourism that relies on skiing, snowboarding and other winter sports. “Having less precipitation might be more of an issue,” he says.

Comments