Wolves and Wolverines

My name is Jon. I don’t call myself “Howling Wolf” or “Running Bear”, because I was born and raised WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) and there is no sense pretending otherwise. Jon. Named after some dude, Jonathan, who said something so catchy that he got into the Bible, which is a massive PR coup, way better than the best Tweet or Facebook post imaginable. Yet, at the same time that I cannot, and will not, deny my roots, I do have a fondness for the aboriginal way of viewing the world — if you highlight the good stuff and forget about the constant warfare, occasional cannibalism, frequent gender inequality, practice of slavery, early death from injury and disease, and other facts of hunter-gatherer existence that some WEIRD romantics tend to ignore.

So let’s look at the good stuff. Most of the time, when we see wild animals, they are running away, fearful of that upright, meat-eating, strange-smelling creature in its environment. Very occasionally, a wild animal stops to look at you. Over the decades, I have been fortunate enough to stare at close range — eyeball to eyeball — with wolves, polar bears, dolphins, whales, ravens, and one crocodile. The encounters happened. That’s factual. But now, we get to interpret those encounters, and that’s where the fun comes in. For example, when Erik Boomer and I were circumnavigating Ellesmere Island, in the Canadian High Arctic, we saw a white wolf, almost precisely when we crossed the 80 o North Latitude line. The wolf hung around camp all evening, slept a few meters from our tent, and was there in the morning, looking at us when we unzipped the vestibule.

So now, “What was that wolf thinking?” Some biologists argue that we can’t even ask the question, because any answer would credit the beast with human emotions – anthropomorphisms — like fear, anger, curiosity, love, and so on. On the other hand, I have traveled enough with non-WEIRD people to know that those who live closer to their hunter-gatherer roots believe that the environment is alive and animate. Every rock, piece of grass, and stick has a story to tell, if only we would listen. And certainly animals talk to us, and we can talk back. But it doesn’t end with idle chit-chat. Some animals are direct messengers from the Other World.

I believe that the Ellesmere wolf was a Spirit Wolf, welcoming us as we crossed 80o, from the High Arctic into the Polar Zone. And what was this wolf saying as it stared at us, head down, ears up, front legs spread out, highlighted by fractured ice and more distant mountains? To me, the communication was very clear. This was no Fairy Godmother Wolf. It was not granting us safe passage or promising what it could not promise. This was the Spirit Wolf, “Jon, Erik: Welcome. It’s harsh up here. You’re alone, far from your brothers and sisters; in a land where rescue is difficult or impossible. You’re vulnerable, about to be exhausted, cold, half starved, battered, strung out. You might die. Welcome. It’s good to see you.”

You can call me crazy or delusional. That’s your business and I certainly take no offense. (Just, please don’t lock me up. Being in a nut house would cut down on my ski days.) But, if you seek the conversation of Spirit Wolves, then you see the world as more magical than if you pass through life without these visitors from the Other World.

Ski touring is about steep lines, deep powder, avalanches, couloirs, chutes, glades, cliffs, and big air. But we also must remember that most of the time, when we are out ski touring, we are walking up hill. As a result, you can’t enjoy ski touring unless you embrace the uphill as well as the down. And if you view the natural world as magical, capable of producing Spirit Animals, your daily skin up will be enhanced immeasurably.

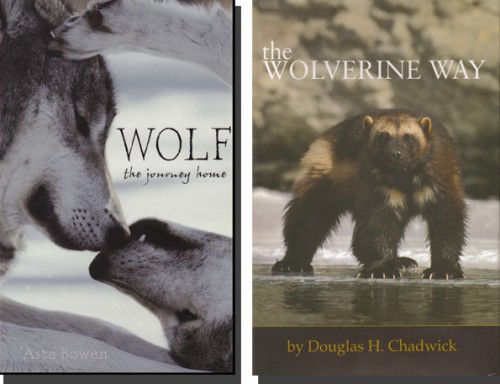

If you’re with me so far, I’d like to recommend two books: Wolf: The Journey Home by Asta Bowen and The Wolverine Way by Douglas Chadwick. Wolves and wolverines live in the forests that we ski in; they hunt in deep snows, raise their babies, and most probably know where we are a lot more often than we see them. Asta paints the family life of wolves: their love, affection, and dependence on one another. Doug sees the wolverine as a thyroid-enhanced, hyped-up loner, a creature that climbs mountains, just to be on top. Both authors speak eloquently of the spirit of wilderness and the destruction of that spirit by the encroachments of this oil-soaked, internet crazed commotion that we call Western Civilization.

Most of the people who read this article are WEIRD. You and I were born that way. We can’t help it. But we can enrich ourselves and the planet by viewing the world as our ancestors saw it, magical and full of wonder.

Comments