La Nina ended in April

An El Niño event, usually associated with significant changes in rainfall, is likely to develop this month and next in the Pacific, affecting global climate patterns, the World Meteorological Organization said on Tuesday.

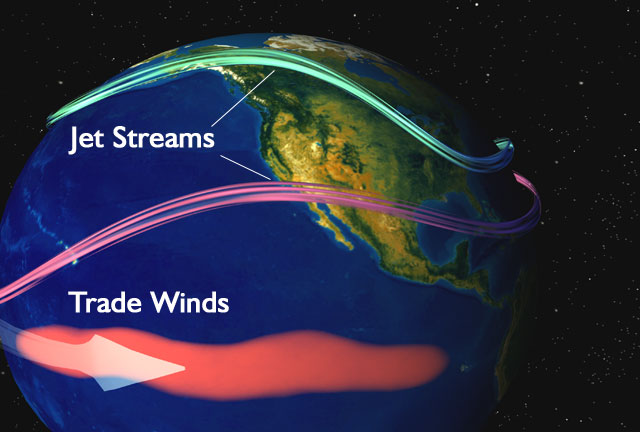

Image above: The image shows what happens when a very strong El Nino strikes surface waters in the Central equatorial Pacific Ocean. The sequence shows warm water anomalies (red) develop in the Central Pacific Ocean. Winds that normally blow in a westerly direction weaken allowing the easterly winds to push the warm water up against the South American Coast. Click on image to enlarge.

The phenomenon, characterized by unusually warm ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific, has been linked previously to drier-than-normal conditions in Australia, Indonesia, the Philippines, northeastern Brazil, southeastern Africa and parts of Asia, the United Nations agency said.

“A weak El Niño may develop in September and October and last until the northern hemisphere winter,” the WMO said in a statement.

El Niño winters tend to be mild over Western Canada and parts of the United States and wet over the southern United States, it added.

La Nina, its opposite phenomenon which causes an abnormal cooling of waters, ended in April.

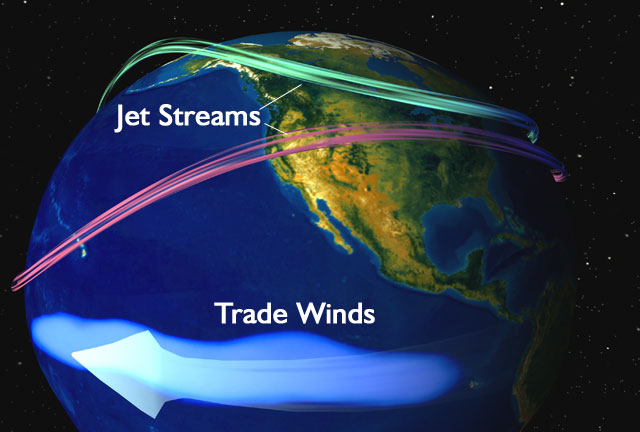

Image above: This image shows colder than normal water (blue) anomalies in the central equatorial Pacific associated with La Nina. Stronger than normal trade winds bring cold water up to the surface of the ocean.

The WMO update is based on many climate forecast models gathered from centres around the world.

“The majority of these climate forecast models say that there is a ‘moderately high likelihood’ of an El Niño. Having said that, it can’t be ruled out that neutral conditions may continue,” WMO spokeswoman Clare Nullis told a news briefing.

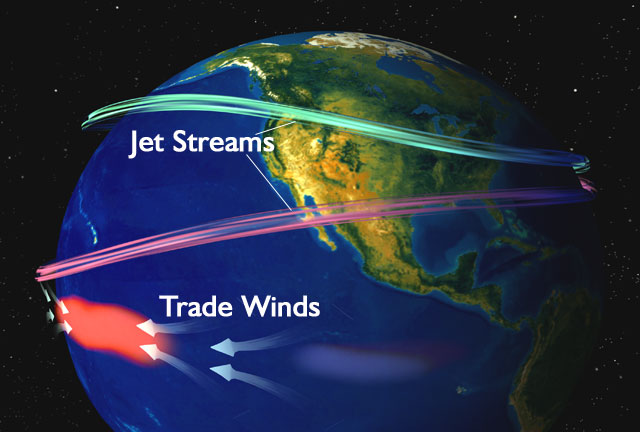

Image above: This image shows the current El Nino’s split personality. Warm waters develop in the central Pacific Ocean. In this case, the warm water anomalies tend to stay in place in the central Pacific.

The Geneva-based WMO promotes cooperation among its 189 member states and their national meteorological and hydrological services and is the U.N. system’s voice on weather, climate and water.

Photo credit: NASA

Comments