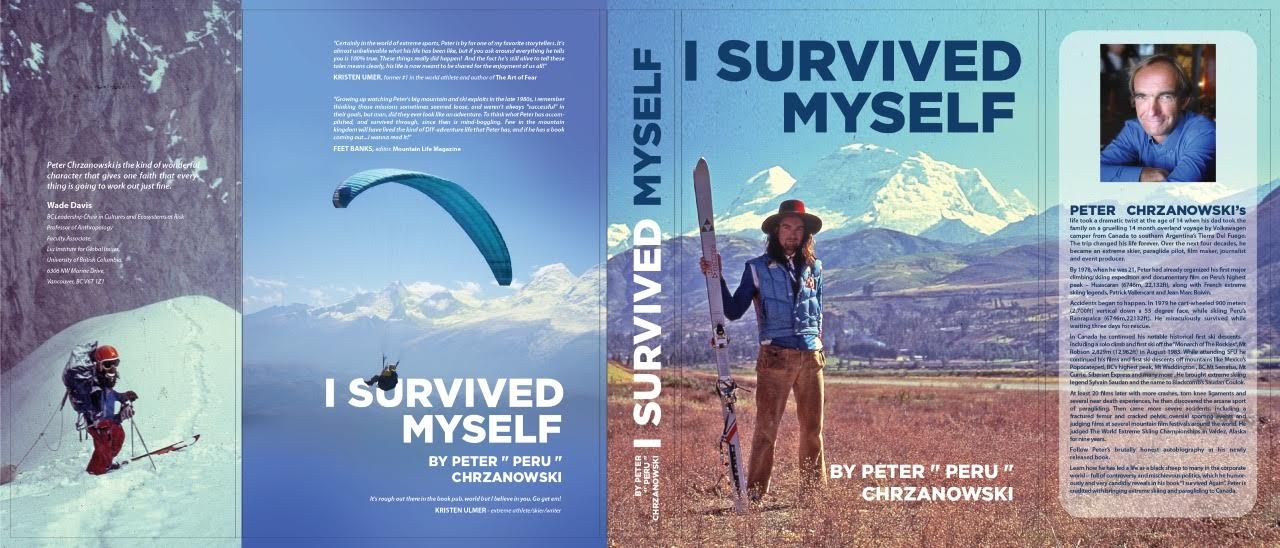

I Survived Myself

Peter Chrzanowski’s new book, I Survived Myself, is a testament to the many lives he has lived. His nicknames “Peter Peru” or “Peter Should-not-ski” or “Peter Chernobyl” are connected to his many ski lives…and these nicknames were earned prior to his taking up paragliding!

His journey is a testament to a life lived on the edge of possibility. From immigrating to Eastern Canada from Poland to embarking on a solo odyssey from the tip of Chile and back in a van, from soloing a first ascent to pioneering groundbreaking innovations in the ski film industry—all before the age of thirty—Peter has lived multiple lifetimes in one. And now, well into his 60s, he shows no sign of stoping.

Exposed to the towering peaks of Peru, Chile, Argentina, British Columbia, and Alaska during family holidays with his parents—a geologist and a survey engineer—Chrzanowski found himself in Peru at age 17, assisting his father with geological work for a Canadian mining company.

“The work base itself was over 4,000 meters in elevation,” he recalls. “So I’d climb and ski the surrounding glaciers on my time off. My first ski descents of the Andes started there, in 1976. I enjoyed the heightened sense of fear that the high alpine environment evoked in me. I discovered that I skied better—more precisely and technically—when I was risking my life.”

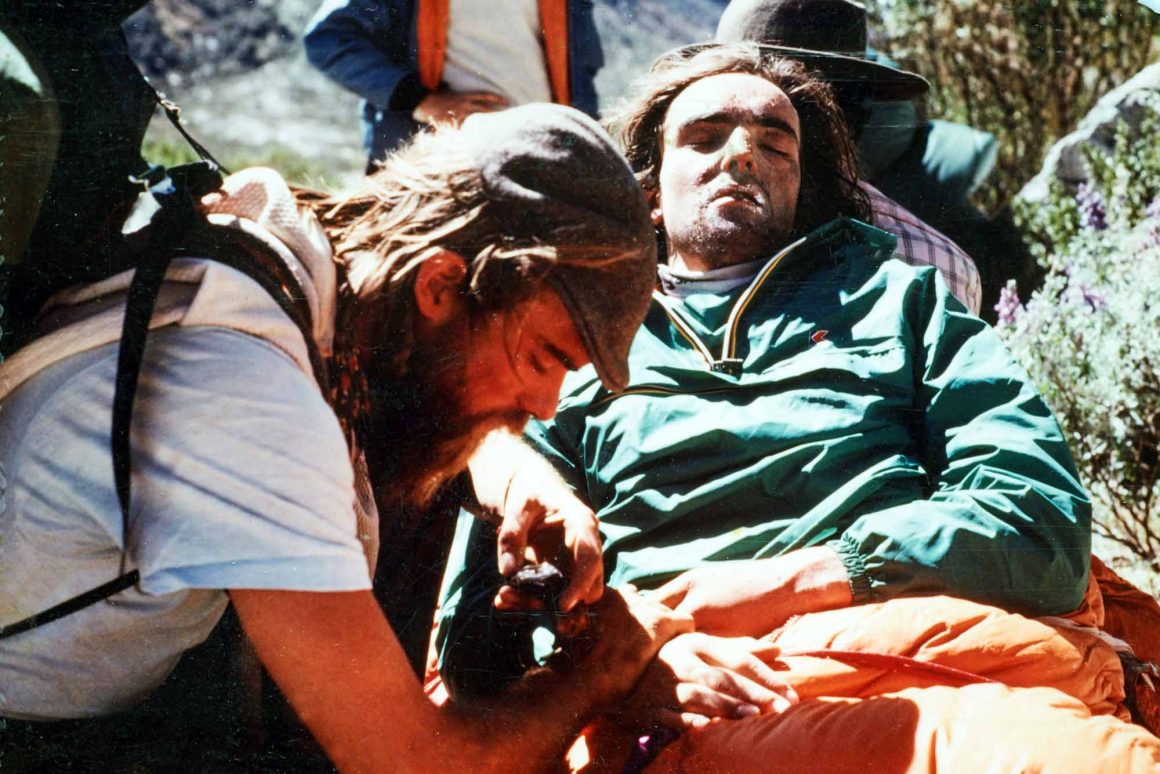

In 1977 he fell 700-metres and was deposited him into a crevasse while attempting to ski off the summit of Ranrapalca (6,162 metres /20,217 feet) while in Peru. The name “Peter Peru” stuck following these adventures.

Following a paragliding incident in México many years later, he did pause to document his collection insane memories and stories from his life, thus commencing the writing process of what became “I Survived Myself.”

“I had a bad paragliding accident, and I was really angry at myself, actually. I needed to focus on something while I recovered in Mexico. I basically wrote it kind of out of anger in about six weeks.”

“I was by myself in a little cabin in Mexico,” he recalls. “And I wanted to do it while I wasn’t bothered by anybody, where I could focus on it. I wrote 14 hours a day sometimes.”

Peter’s life has been defined by adventure since his earliest days. From childhood aspirations to stand out as an immigrant in Fredericton, NB, and as an only child, to spending almost a year, and several subsequent summers, living, working, and exploring South America as a teen, Peter’s formative years were nothing short of transformative.

“During the long trip being away from my friends, I had a lot of time to focus on reading and getting to know the places we were visiting. My whole focus changed, and interests changed. That definitely made me a different person. I mean, that trip to South America and working down there as well, every few summers made an impression on me.”

A longtime friend of Peter’s, and Chamonix legend Sylvain Saudan, describes Peter as a “locomotive”—an adventurer always ahead, launching new projects, and igniting enthusiasm. Despite setbacks, Peter never gave up, displaying incredible resilience—a beacon of inspiration for today’s youth.

As one of the first of his kind in the ski and adventure filming scene, finding ideas and coming up with new concepts for projects was a practice in creativity and thinking on the go.

“We were always looking for stories,” he says. “My first film was really just a trip I had organized with friends. We knew nothing about the filming part, we had a film crew who took care of producing the film. But there was so much more to craft the story around. That’s what came more easily to me, the story telling.”

Despite facing myriad highs and lows throughout his 40 plus year career, the projects that hold emotional and sentimental significance stand out to him the most.

“I think the film I did for Trevor Peterson, In the Spirit, really stands out to me because Trevor was a close friend. When he passed away, it really impacted us a lot. And that project was kind of magical. I hardly received $5,000 advance from a distributor which is nothing to start a film. I went to Europe with Troy Jungen who had a network of friends there. I went without a camera, just carrying tapes, and everywhere we went, people helped out by lending me cameras, and I met film crews who did interviews for me and everything kind of fell together as if Trevor’s spirit wanted us to make the film. So, that project is important to me and was really memorable.”

Peter grew accustomed to starting projects off underfunded and under situated. When faced with these tougher moments, he largely relied on friend networks and the kindness of people to make everything run smoothly.

“It’s tough,” he reminisces on the hustle of low-budget film making. “You know, I think that under funding just make you more creative, you have to look for alternative ways to get to the desired outcome. When we made our North Face film, I think I had three television stations participate. One station gave us the cameras to use, another one helped with sound and editing, and another one the narration and some other assets.”

“And to put things together when I was making the Golden film on the history of Kicking Horse it required a lot of a lot of stock footage and politics. I was worried that I might get sued by the corporation that was making the resort because I really didn’t like the way they were going about it. Every story kind of had its way.”

With all of his adventures and escapades making films and skiing extreme lines, Peter needed a proper home base where he could experience great adventure.

“My family bought land in Pemberton back in the 80’s and we just kind of sat on it. Luckily its value went up and we were able to subdivide and build a home and that’s where I’ve been for the last 15 years. I really like it. It’s a little quieter, but still close enough to where you can find some action.”

Action is something Peter has never been short on. He began his career of delving into the critical and extreme as a skier, but as he writes about in I Survived Myself, extreme paragliding quickly became part of his repertoire. It’s not always the case that we get to feel the weightless, flight-like sensation of skiing powder. Peter’s way to avoid this little problem was to take to the skies.

“It was horrendous weather and windy. And we just found a hill to jump off and give each other rides back up with a car.”

“When they broke out, I had been hearing that paragliding was really like skiing powder, and I wanted to have that weightless, flying sensation. I was introduced to paragliding by a famous climber Mark Twight who was working with a company called Wild Things in the US. They had developed a paraglider – copied a French design. He brought those to BC in the fall. It was horrendous weather and windy. And we just found a hill to jump off and give each other rides back up with a car. I tried a few flights and liked the feeling and I really liked the idea of hiking up something and then not having to hike down.”

“That was kind of our introduction in ‘87 in the fall. And then I hiked and flew off things for 15 years or so.”

And in those 15 years, Peter went on to go on some incredible flights all over the world. Many of which were risky descents off high elevation peaks.

“Though I didn’t really start learning how to thermal till after 2000. Technology got better around then, and I realized I could actually stay up there for ages and go cross country. That’s when it really got interesting.”

Using pockets of hot air to climb up low-density air columns is a technique called thermal paragliding – used to take longer flies both in duration and distance. Cross country paragliding became more and more a part of Peter’s life over the years. Though he spent his early years paragliding making more ambitious attempts at technical flights, he has now shifted a bit in his practice.

“You know, now I’m 66 years old, and I really have to tone it down these days. Now I just fly for pleasure, really. I don’t do risky crossings anymore. Now adays, I have been taking it easy and looking forward to doing other things. I did a few film workshops out of my house in Pemberton – I may get that going again. My publisher is also trying to talk me into doing another book!”

After all was said and done, Peter says he’s just happy to have completed another life goal and milestone. “It just feels really nice. You know, we all want to leave something positive behind and I hope I’ve done that with this book.”

Comments