Why Zincton Resort Matters: A New Model for Communities

One week after Wildsight launched a legal challenge to force Zincton Resort into a full environmental assessment, founder David Harley delivered a blunt message: if the court challenge succeeds, Zincton is done.

The reaction underscored what has long been true in the Selkirks: this debate isn’t just about process. It’s about the future of rural mountain communities that sit at the intersection of recreation, conservation, and economic survival.

Wildsight argues the province erred in deciding Zincton did not require an environmental assessment. The province concluded that the project falls below the threshold that triggers one — Zincton proposes fewer than 1,700 beds, under the 2,000-bed requirement in provincial law — and that the Mountain Resorts Branch has the tools to manage the review. Wildsight wants the courts to overturn that decision.

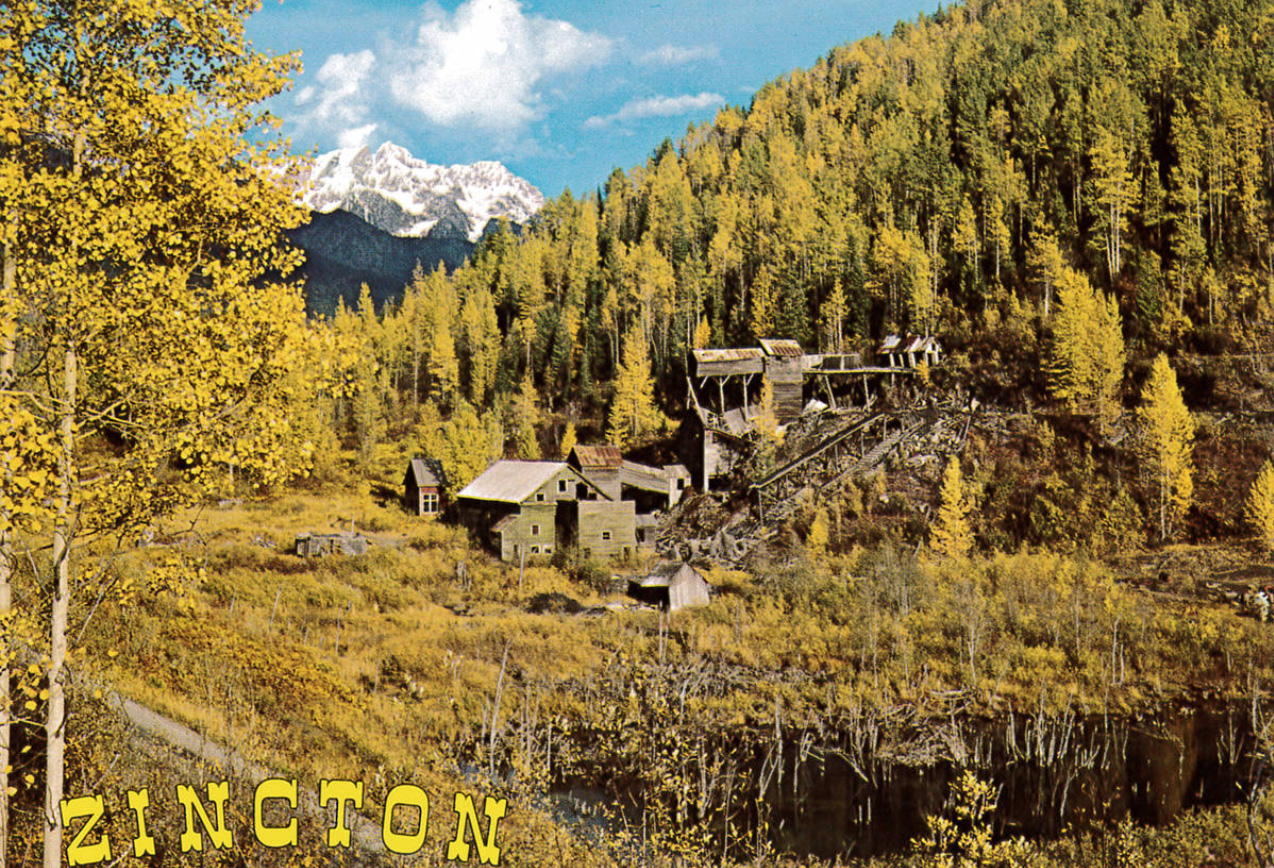

Harley maintains the project follows the law as written and that forcing a multi-million-dollar assessment would kill a proposal intentionally designed to be small-scale, privately backed, and community-focused. He points out that most development sits on private land, the plan includes cleanup of legacy mining impacts, and the resort is built around strengthening the year-round economy of New Denver and nearby towns.

Critics will claim his refusal to fund an unnecessary EA signals bad intent, but the facts point the other way. Zincton was deliberately designed to fit the province’s rules for low-impact mountain projects. Declining to spend millions on a redundant process isn’t avoidance — it’s common sense. The project’s intent is already evident in its design: restoring mining scars, improving water quality, limiting the development footprint, and building a resort model centred on ecological health and community stability.

That model matters. Zincton represents a shift away from the mega-resort playbook and toward a new kind of mountain development — one rooted in sustainability, restraint, restoration, and rural revitalization. It begins with cleanup, not construction. It emphasizes quiet, controlled backcountry-style skiing over high-volume infrastructure. And it directly addresses the needs of small communities facing declining school enrolment, hospital pressures, seasonal employment gaps, and limited housing. For places like New Denver, a well-designed recreation economy is not a luxury; it’s a lifeline.

Across rural B.C. expectations for new projects have changed. People want developments that repair landscapes, minimize impact, respect Indigenous values, strengthen communities, and provide stable year-round jobs. Zincton aligns with that modern standard far more than most proposals in the province.

Wildsight’s challenge, however, is rooted in an anti-development ideology that has become the organization’s default stance. It opposes projects of nearly any scale, even those grounded in restoration, low impact, and community need. While framed as environmental protection, its position no longer reflects the balanced, sustainable recreation economies rural British Columbia requires.

This is why Zincton matters. The project is a test of whether B.C. can support a new generation of small-footprint, environmentally restorative mountain developments that blend ecological repair with rural economic resilience. Wildsight argues the review was insufficient; many in rural B.C. believe the opposite — that the challenge ignores the real social and economic pressures facing mountain communities and dismisses the public’s growing expectation for innovative, restorative recreation models.

The B.C. Supreme Court will now decide which vision prevails. A ruling against the province could reshape how future mountain projects are evaluated and whether small, sustainable, backcountry-oriented resorts have any viable path forward.

Whatever the outcome, the Zincton case will influence how communities, conservation groups, Indigenous Nations, and developers navigate the next generation of ski and backcountry projects in British Columbia — and whether rural mountain towns will be allowed to build the future they need.

Powder Canada Editors

Source/photos: Wildsight, Zincton Resort

Comments