La Liste: Everything or Nothing

Back in 2016, free-skier Jérémie Heitz compiled a list of some of the most daunting and iconic peaks in The Alps’, to then freeride down them at record speeds. Having developed a taste for adrenaline, the Swiss skier, known amongst his peers as the fastest free-skier in the world, collaborates with his close friend Sam Anthamatten to set off on an ambitious new endeavour, that will take them across the world.

La Liste: Everything or Nothing is available for video on demand. Hit the link to watch the culmination of numerous winters: https://www.laliste-everythingornothing.com/buy-now.php

The plan is simple, but by no means safe, as the duo write up a new shortlist, this time of some of the most awe-inspiring, intimidating mountain ranges on Earth, finding high-altitude peaks that surpass 6000m, taking the notion of steep-skiing to a whole new level, and redefining what it means to be a free-rider. On this journey, which takes them from the Andes mountain range in Peru, to the Karakoram in Pakistan, Jérémie and Sam set off on the trip of a lifetime. Though what goes up, must come down – and in their case, it does so at a frightening pace. This documentary joins them on their mission, as they strive to show off the natural beauty of the landscapes, the grace of the skiing, but conversely, the dangers that come with it – as they test the boundaries of human possibility. For these two men the scenario really is simple: it’s everything or nothing, and it seems like there’s rather little in between.

CHAPTER ONE – THE EVOLUTION OF LA LISTE

Back in 2016, Red Bull Media House produced a short film entitled La Liste, where esteemed freerider Jérémie Heitz set off to find some of the steepest descents in the Swiss Alps, as high as 4000m, compiling a short list of locations he intended to ski down. Succeeding in his attempts, adrenaline seems an addictive force, as he returns, alongside good friend and fellow skier Sam Anthamatten, to surpass their previous accomplishments, this time touring the globe, with a hugely ambitious attempt to ski 6000m peaks.

“This project is following on from the first film that we did in the Alps, where we would ski next to my house. Then Sam and I both decided to bring all of our freeriding and big skiing to a higher altitude. The goal was to ski 6000m in the Andes, so we basically wanted an evolution of the first film,” Heitz said.

“I was first approached by Jérémie when we finished La Liste,” Anthamatten added. “After the first film, straight away our minds were already on the next project. We wanted to go further and bring this to another level, and that’s how it went. We were really keen because of the team we put together, we had a great team to push limits.”

But accomplishing such remarkable achievements in extreme sport, is nothing without a talented and diligent crew documenting their journey, and with higher ambitions comes greater responsibility, and the skiers needed a committed, and larger-scale company to bring their story to life. It’s here they found Canadian production house Sherpas Cinema, and in particular, the filmmaking duo of producer Malcolm Sangster, and director Eric Crosland. But these new collaborators were not mere strangers.

“The two main characters, Sam and Jérémie, are long-time colleagues and friends of ours,” Sangster explained. “We worked with Sam through various North Face films and with Jérémie through some Audi stuff, so we knew those guys well. Jérémie had produced the first La Liste film with local Swiss filmmakers, so when it came about and his career blossomed and Red Bull got involved, they wanted to make a follow-up film, and we were essentially approached by Jérémie and Sam and Red Bull, and that’s how we kicked it off, and that was back in 2018.”

Working with Sherpas was a great relief to Heitz, who not only appreciated their ability to take their story to a whole new level, but also admitted that their involvement removed his responsibility from a logistical standpoint, allowing him to focus more so on the skiing, and yet still have the freedom to contribute editorially, and ensure his voice was heard.

“We thought we wouldn’t use the same production as the first film because it’s my friends, they are small in terms of organization and resources, so we agreed there was no way they could handle this project, it was a bigger one,” Heitz said. “So I directly contacted Sherpas Cinema because they were the best on the market. It’s been much easier for me this time because all the reservations with things like the media, was much more their job than it was for me in the first film,” he said.

“We are reserving a new cut every two weeks of what they are editing and we can give our advice and if we want to change things, we tell them, and we are pretty free about it, and they are listening to us, which is nice.”

For the director Crosland, tasked with making this a more cinematic endeavour, this project is not so much a mere expansion of the first project that came before, but instead La Liste: Everything Or Nothing is more of an evolution, and very much a standalone project of its own right.

“It’s the evolution of the first one,” Crosland said. “But the film is totally different, because this is really a documentary, it’s not like a sports highlight video in any sense, it’s a true documentary. But the idea of it is an evolution of what they tried to do in the first film, but a completely different style of filmmaking.”

“If you ask Jérémie’s hardcore fans they’re going to assume it’s a sequel, especially with the title, but we like to think of it more like a series, like James Bond or Star Wars,” producer Sangster added. “You’re still under the franchise of La Liste, but it’s very much standalone, we’re a completely different film entity than the group who made the first one, which was a little more rooted in core action sports and core skiing, whereas ours is based around the subject matter of skiing, but it’s going to be more of a global expedition, exploratory film.”

What helps achieve this goal, is having a filmmaker like Crosland on board, who is driven by characters, and story, above anything else. Sangster explains that this has been a common, and consistent goal at Sherpas, even since their inception.

“We did feature films in the ski genre, and one of them was on climate change, ten years ago now, and the other was about the process of the human mind, and that inner psyche,” he said. “I think at that time we were always attracted to action sports films with a little more of an interesting story. Before that you didn’t really have that, it was like montage music videos put to skiing. So we started doing that and viewers really cottoned on, and now essentially every action sports film has more of a message, so the genre has changed. Every brand we work for these days, it’s about storytelling, rather than just straight action snow montage material. That’s where we’re really trying to do here with Jérémie and Sam, to have the viewer relate to them on the best level they can and their struggles as they travel to the mountains.”

For Anthamatten, this made Sherpas, and in particular Eric Crosland, the perfect fit to helm this project.

“Eric is well known for his artistic cinematography,” he began. “He is not an alpinist so I saw him a few times getting to his limits and it’s also there where you can see the real human in the film. At the end he’s always super focused on what he is doing, it’s always about the shot. It’s like an obsession, or perfectionism that he is searching in cinematography and we are searching for in the skiing.”

“I knew Sam from working on some other projects with him,” Crosland said. “He asked me if I was interested in helping make the project come to life.”

However Crosland’s established relationship with producer Sangster goes back a little further. “I’ve known Malcolm since I was a small child,” the director smiled. “I’ve known him my whole life and he’s one of my best friends so we’re pretty much like brothers, we know each other so well. He didn’t come on any expeditions, or any of the film shoots but he was working hard behind-the-scenes the entire time and he’s a really talented producer and a really great communicator, so I thought it was safer going into the mountains knowing that he had our backs.”

“My first ‘meeting’ with Eric was when we were 12 years old,” Sangster added. “Eric and I are lifelong friends, we went to school together, so we go way back. We started this company Sherpas Cinema back in 2006, so we’ve been working together for a long time and when this project came about Eric had worked a lot more closely with Sam and Jérémie over the years, he was the go-to director for this project, and we teamed up and we went from there.”

So now with the filmmakers in place, the subjects set and ready to go, all that was left was support from Red Bull, and as Crosland explained, their help was invaluable.

“Red Bull have been amazing,” he said. “They’ve made a really creative environment for us to produce and be creative in, and they have an amazing facilities in Austria where we mastered the whole film, in their sound studios. They’ve invested hugely in developing and creating a really fertile environment for creatives to bring their films to life.”

Sangster echoed the sentiments of his director. “It’s been fantastic, a really easy working relationship. Of course we’re across the Pond with the folks in Austria there so there’s always the time and language barrier, but it’s been really smooth. Red Bull are well positioned in the action sports world” he finished.

CHAPTER TWO – GOING TO THE LIMIT

There is something endlessly fascinating about watching Jérémie Heitz and Sam Anthamatten chase their dreams; the pushing of their limits, and taking humankind to places we barely dreamed possible. For the courageous duo, putting their lives on the line so frequently requires an element of trust, and that’s something they share, an unspoken agreement they’ve made right from the start of their friendship.

“I came to know Jérémie in Italy on a freeride qualifier,” Anthamatten says, while recalling their first encounter. “You go to those competitions and you look around for someone you might know, or want to know. I had an incredible first impression of Jérémie when he did a huge cliff, and won the competition, and I fell face down. That was our first meeting, and it’s special to speak about now because at the time we didn’t think we were going to grow together this far.”

“It’s difficult to have people joining you on such amazing trips, and on such difficult terrain, and I don’t have many friends who can follow me,” he continued. “To find a companion who is able to climb 6000m peaks and is able to ski on it, it’s rare, so to be involved together on these projects is super fun.”

Heitz explains too that he works in unison with Sam, often on the same page when it comes making important decisions.

“Every difficult decision we have to make in the mountains, is almost always the same decision I would make, because we know each other and we know the most important thing is to go back home safe,” he said. “We know what each one is capable of, or not, because we’ve been skiing together for a long time now. It’s really useful when making decisions.”

Not only is skiing down 6000m peaks rare, but also incredibly difficult, and requires a certain level of professionalism and perfectionism to pull it off – which Crosland believes this duo carry.

“Jérémie is a very thoughtful person, a perfectionist, he’s really professional and a kind person. Sam is down to earth, and has a very good sense of humour, incredibly talented and has a deep understanding of production.”

“I really enjoyed working with them, I knew how strong they were in the mountains having seen Jérémie’s first film. They are a dream team and I wanted to see these guys try and move the bar of the free skiing realm.” Crosland said.

“Sam and Jérémie are great,” Sangster added of the film’s two compelling subjects. “They bring a wealth of experience to these expeditions. It’s very serious stuff they’re doing, trying to ski 6000m peaks, but what is so great about them is that they keep it light, they’re pranksters, they’re jokesters, and they do a good job at keeping the mood and tension light, so they’re fantastic to work with in that regard.”

“But I think this project for both of them was an eye-opener. Those guys have been pushing it a lot their entire careers, wondering where that limit is, and I think as you watch the film you start to realise that they’re starting to find that line of what is acceptable levels of risk for them, so it’s a bit of a coming-of-age piece for those guys. So we saw this character development right before our eyes over the last four years.”

It’s not just Sangster and Crosland in constant contact with the two skiers, as the team that set out to these breath-taking landscapes around the world also consisted of a handful of other crew-members, one of which was Josh Lavigne, the cinematographer of the piece, who excels in high-altitude environments. Part-filmmaker, part-mountaineer, he too admits that the boys left an indelible impression on him.

“Working with both of those guys was really good,” Lavigne began. “One of the big things about any long trip and expedition is how you get along with someone, how you interact with them and if it’s really intense all the time, it’s harder to relate, it’s harder to become close, but with Jérémie and Sam there’s no doubt that those guys are out there to have fun. For sure they’re objective and the seriousness of the consequences are at the forefront of their minds, but at the same time they know that if they’re not enjoying what they’re doing, then what’s the point?”

“They have a really good bond with each other so they can communicate well and come to good decisions,” Lavigne continued. “But they were able to bring me into the fold of their decision making, they always asked what was important to me, because I was just as exposed as they were, and that was really important to give me the space to make my opinion heard because I am just as effected by those decisions as they are. They were also open to what I had to say from my experience with altitude and acclimatisation so that really helped the team coalesce and become a unit,” he finished.

Given the conditions the crew faced on their expeditions, a strong sense of camaraderie is essential to ensure they have a good time, and vitally, their material is as strong as it possibly could be.

“One of the most crucial elements is the crew dynamics,” Crosland said. “You’re living high altitude for months at a time, sharing tents, sleeping inches away from these people, and having to communicate in incredibly stressful situations, so you have to have a base level friendship and respect for this dynamic to work, and we tried our best to choose people we could do that with.”

This teamwork extends beyond the field, and all the way back to the hardworking team in Canada, doing an incredible amount of work to ensure the crew have everything they need to shoot the film as best they can, and capture the footage they intended to shoot. For Sangster, this is where that lifelong friendship with Crosland came in rather handy.

“It’s easy for us to be on the same page,” he said. “Especially during this day and age where a lot of us are spread apart. But Eric and I know each other so we don’t have to book phone calls or anything like that, we just text and call each other, it’s an easy working relationship that way. Things are certainly hard to produce, especially this subject matter, travelling around the world and skiing off these peaks, so any sort of close relationship between the producer and director really is beneficial.”

Another key piece to this jigsaw, also working on the film back on Canadian soil, is editor Tim Symes, and he discusses his process, and how even though he works from afar, often somewhat isolated, he is still very much singing from the same hymn sheet, and is also pleased to be part of a system that benefits their creative work.

“I like to work with a streamlined feedback system so anything that comes to me, comes from Eric, and he’ll distil any feedback that is coming from producers, and I just work closely with him so we’re not creating a film with a hundred different voices coming straight to the edit,” Symes explains.

“Editing is the weirdest role of the lot because I don’t get to establish a lot of those relationships in the field,” he continued. “When you’re out there you’re trial by fire, you forge these really strong relationships, but I’ve been really fortunate enough to have that with Eric and Malcolm on various trips that we’ve done, and not necessarily in the film industry but just as friends and working together so closely for years, and that friendship allows for honesty, it allows for your opinion to not be filtered every time. When you’re working with friends you can be pretty upfront about what needs to be done and what you think should be done about certain things, and we tend to agree so it doesn’t really become a problem anyway.”

What drives this entire project, ultimately comes down to what drives the subjects at the centre of this narrative. The perpetual, unanswerable notion of what pushes us to these limits. For Heitz, it’s all he’s ever known.

“I was born in the mountains, maybe if I was born next to something else it would be different, but when you’re born in the playground that you always knew, for me it is natural to use this playground next to my house to express myself,” he said. “When I look back now, the evolution has been smooth, I took part in mountain racing and I did some competitions and every season I wanted to push a little bit more, so it’s natural that we want to go a little higher every time, it’s been like this my whole life. So for me it’s not a super risky thing.”

“What drives me are those feelings,” Anthamatten added. “When you have a project that is easy and you realise it, it’s cool. But if you have a project that is really demanding and you’re pushing your limits, that feeling of success, of flying down the mountains and it actually works, it’s amazing, and it’s addictive. It’s not that I want to have the adrenaline rush, I think adrenaline is part of it, but it’s really searching that impossible thing that is still possible, if you make the right decisions.”

Even Crosland, who you wouldn’t catch freeriding down a mountain side himself, can see the appeal in their quest.

“I think for skiers it’s a really hard thing to articulate what drives these people and there’s a really powerful allure or force that draws people into the mountains,” he said. “Them as subjects are still trying to figure out where that passion is coming from, but I think it’s deep-seeded human instinct to be drawn into the mountains that is pulling them to higher mountains and deeper into the wildest landscapes on the planet.”

“I think it’s interesting for audiences to see what athletes have to do to raise the bar in their particular discipline and particular sport. What type of toll that takes on any athlete and I really just wanted to tell the truth as it happened and let people make decisions and opinions. I just want to tell the truth and show how crazy and dangerous you have to be, and how much passion you have to have to be able to push the bar in any sport.”

Meanwhile, Lavigne sees things in a unique way, believing that this instinct to push ourselves to the limit is actually helping to push mankind as an entire race, and that we need people like Jérémie and Sam in order to do so.

“The risk-taking behaviour in somebody who is exploratory and extremely able to perform under those sort of risks, is a special quality that only a few people have,” he began. “It belongs in our society. We need to have individuals that are not only able to perform at that high level, through mental and physical training and experience, but also they are allowed to have those visions and those dreams to go and explore and do something that is just for the style and for the sake of doing it, and not because it’s a massive scientific discovery, or it’s going to make them rich.”

“There’s an inner part of human genetics that requires us to search and go beyond what our limits are, to evolve as a species,” he continued. “They are pushing themselves and pushing the boundaries of what is possible skiing, and the physical limits of what is possible for a humans. This highlights a defining part of the human species that is really unique and special. I think we should acknowledge that they do have a place, not only for the inspiration of humanity but also to keep us moving forward with what is possible in our minds and our bodies, because it really does push both of those boundaries,” he finished.

CHAPTER THREE – RISK VERSUS REWARD

As the title alludes to, what audiences see in La Liste are people genuinely risking their lives. What transpires is a thrilling ride of a film, but the fear factor that is prevalent cannot be ignored, as viewers will seek to understand exactly why the likes of Jérémie Heitz and Sam Anthamatten are willing to put everything on the line in the way that they do. For the former, safety is a paramount concern throughout their travels, even if he does feel an element of pressure to deliver strong material for the film.

“You need to be professional in your mind and not push too much in the mountains,” Heitz said. “You can always come back. But if you make the wrong decision or make a mistake you don’t have the chance to come back, and these kind of things have to be clear in your mind. It’s tough to deal with it, because now there is Sam involved, the cameras are involved, they are travelling for you, and of course you want to deliver something during the expedition, but you need a balance.”

For Anthamatten, he explains that when he’s performing for the cameras, he has to try and ensure he doesn’t change anything about his style of skiing purely for entertainment value.

“When the cameras are watching it’s more about the timing,” he began. “But otherwise when you know the team so closely, you make the same decisions as you do when there is not a huge film team there. It’s important in those mountains because you can’t push your limits just because there are some guys standing there with a camera, you cannot risk your life because there is a camera pointed at you.”

It’s not just a stressful ordeal watching this film as an audience member, as even director Eric Crosland admits that while shooting the film and capturing this remarkable content, he too is anxious about the safety of his subjects matters, who he also considers friends.

“It’s incredibly stressful, what they are doing is one of the most dangerous things you can do in the mountains, it’s more dangerous than mountaineering or alpinism because they have to descend at such high speeds, at such remote locations, un-roped,” he said. “It’s the most dangerous type of filmmaking I’ve ever done in my life. At altitudes that are incredibly uncomfortable. It’s absolutely, insanely stressful watching them climb and ski, because at any one moment they could lose their lives, and I’m just usually sitting across the valley, watching them on a drone and it’s just so stressful until they’re down safe. In the film you see what happens when you make mistakes or become unlucky and it’s real and can be really devastating.”

Sangster also admits to having that fear, but concedes that as a documentary film crew they have an obligation to maintain a sense of journalistic code, to follow the events and not seek to alter them in any way.

“We leave the decisions with them, we’re very much a documentary crew in that sense, when it comes to the day on the mountains, whatever happens, happens,” he said. “It’s an immense level of risk and in our very first expedition, we had an accident. That was a big eye opener of what can happen and leading into the subsequent expeditions from there, there was always that constant balance of wanting to be successful in the project and the film, but keeping that balance of risk versus reward and keep in mind what is worth it. But when they get down safely people breathe a heavy sigh of relief.”

“So many films we watch these days, and on social media, are all about going out, crushing it, or killing it, and there is a discussion around risk but the side you don’t see as much are these accidents and the heartache that can surround them. I think that’s what the third act of this film portrays. This is an internal discussion about where that limit is. Everyone is going to have goals and you’re always going to keep dreaming, but what are you willing to sacrifice, your family? Life, love, career? I think it’s an interesting discussion for all walks of life.”

Though feeling a duty to show the truth of the story at hand, for editor Tim Symes, he does admit to feeling a sense of responsibility in depicting these events in a way that doesn’t glorify it to the viewer.

“I didn’t grow up in the mountains but I’ve always had a fascination, especially since I moved to Canada, and it’s prevalent, there’s a lot of tragedy, and I don’t necessarily like the glorifying of it,” he said. “When you get an honest take, an honest opinion when people are really laying down what could go wrong, what the mountains are like, that’s what I am interested in as a storyteller and a filmmaker. We are custodians of presenting these films to people, and there are people who watch them and there are people taking influence from them, and I think it’s responsible to show risk versus reward, so people know the real consequences, and the truth behind it.”

In La Liste: Everything Or Nothing, that very much proved to be the case also, following one difficult sequence in particular, depicting a near-fatal incident. This moment is one that cinematographer Josh Levigne struggled to make sense of, while also examining his own safety when shooting on location.

“It’s like being a war journalist, we need to be an observer and document, but separate ourselves slightly from the subject. We did have an accident and we did film and watch what was happening and that played on my mind after the accident. I think what was important for me was to ensure I was making the right decisions for my safety, making sure I came to trust the decision-making process that the guys had. As long as I felt like I could trust the decisions that they were making, I knew we were doing everything we could to mitigate the risks,” he continued.

“There’s no doubt that free skiing with the speed is on the verge of reckless. But to say you’re not allowed to be reckless, is not a virtue for society. There were skiers in Peru who skied down after us and they skied little jump turns all the way. Their style was more classic, and we could have easily have done that and called it a success, but we didn’t, for Jérémire and Sam, that wasn’t a success. I think that’s something that will be argued and talked about for eternity, because there is no real answer to it, it’s such an individual desire to want to do it in that way, how do you explain that to anyone?” Lavigne finished.

It wasn’t just Lavigne who had to live these experiences by being there in person, as having to edit through the material captured, also left a profound impression on Symes – even if he was on the other side of the world.

“When it comes to cutting the footage, there’s a sensitivity that needs to be employed to make sure you’re seeing a truthful account but you’re not glorifying it, or doing it for the sake of entertainment, you’re doing it because it’s something that happened and it’s important to know what these consequences are, and with the blessing of everyone involved to show that and to show it in a tasteful way, the accident is an important part of this story.” he continued.

“As an editor you have that removal, that separation and it’s so important for me to never get desensitised to what it is I am editing, because when that happens, as a human being with feelings and family and personality, then you can lose what it is that you’re trying to edit. It’s a delicate balance in how you portray that footage, and making sure it’s palatable for audience members as well.”

Though battling these conflicts internally, one thing Symes didn’t have to concern himself with was any sense of physical challenge, but for Lavigne, that was a huge deal – for while we focus so heavily on the subject matters and the risk they are taking, every shot has a camera operator behind it, taking themselves up to high peaks to capture this footage, and ensure the content is worthy of the expedition being undertaken.

“My role was to really be the on-mountain camera operator,” he said. “I’m a mountain guy, but I’ve recently started filming, and it seems like my niche is for doing things that regular camera operators can’t do. My role was to be with the athletes in those extreme environments and try to capture the more emotional moments, the moments you don’t get from a remote camera from across the valley.”

But excelling in such a niche area adds a pressure of sorts to Lavigne, especially as he only ever has one take to get things spot on, given the one-off nature of this tantalising sport.

“There are huge amounts of pressure to get the shot, you can’t just do a retake,” he said. “Some of the ways that we mitigated that were by getting the more traditional shots, then having a second drone in the air, so the production team took that responsibility partially away from the filming that I was doing. To have that pressure to get the shot and be up in that place at the same time were conflicting pressures, but focusing on my safety and getting into a place where I felt comfortable so I could focus on the artistic portion of the day, was really important.”

“When you’re at 6000m and your hands are cold, you have to really take care of yourself and get yourself in a tent, keep your hands warm, keep your batteries on your chest, but outside of those technical components, you have to perform the shot,” Lavigne continued. “Having a bit of a vision to share with the audience of what the most dramatic moment in that specific part of the ski descent is, is really what I was looking for. In Pakistan I knew if I came up behind the skier when he started at the mountain, it would give the audience the real perspective on how steep it is, how exposed it is, how terrifying it is, and that’s what I focused on, those kind of moments, to bring the emotion out.”

Lavigne also admits though, that given all this pressure on his shoulders, and the diligence and sheer courage he had to display, when it all comes together, it’s truly a joy to behold.

“Climbing in Peru, the scenery, the background, the dry and yet snowy summits, to me that moment up there felt not only cinematic but I felt like I had planned for that moment in my mind. When you’re flying a drone at altitude, there’s all these different challenges, the drone might not fly as well, it runs out of battery, the batteries die because they’re cold. When you get that moment when it all comes together, and you see it on the big screen, that’s what it’s about.”

Though this drone footage, which is imperative to this story being told, doesn’t come without challenges, and precautions, as Crosland explained.

“We had to hack all our drones to be able to fly higher elevations, so we had to actually modify them and write code for them and break the height limit on them, so we only had a very small time of battery life to get the shot before the drone had to return down to the ground, and switch batteries, so those guys were true masters.”

“It is literally one of the hardest environments in the world to make films, like being in space, or being sent to Mars,” he said.

CHAPTER FOUR – BRINGING THE ADVENTURE TO LIFE

With a film of this nature, so much of the enjoyment derives from the ability and fearlessness of the subjects, but that doesn’t count for much when not presented in an accomplished and visually striking way. But to do that comes a whole myriad of challenges, as needless to say, it’s not especially straight-forward shooting footage in the snowy mountains of Pakistan, thousands of metres high. To call this project ambitious is an understatement.

“There’s no doubt that it was super ambitious,” said DOP Josh Lavigne. “You’re tyring to ski off a 6000m peak in an equatorial band in Peru and the Himalayas, that has really challenging conditions to predict and you’re going through several thousand metres of different types of snow conditions. You don’t have instant reports from nearby ski descents happening so you can’t rely on information from other experts, you’re going there, you’re trying to give yourself enough time to acclimatise and then you hope that the weather and the conditions come together. In some ways it’s amazing what we did accomplish.”

Logistically, ambition is a word that seems somewhat apt given the sheer magnitude of the undertaking at hand, and much of that lay on the doorstep of producer Malcolm Sangster, who had many plates to spin – especially when you throw Covid into the equation.

“On these mountains you find good snow conditions maybe once every two, three years and we’re trying to mount up a big expedition and film and get that done, so just being that lucky to have the stars align is the biggest challenge,” he explained.

Given the nature of this tale, which is to take both Jérémie Heitz and Sam Anthamatten’s talents around the world, this invariably transports the viewer to the breathtaking and picturesque landscapes of Pakistan and Peru. Though of course in the height of a pandemic, all of the travelling that was required threw something of a spanner into proceedings.

“We just ran into travel ban after travel ban,” Sangster said. “The last act was supposed to be in India, but it was essentially a no-fly, so we went back to Pakistan. When they were in Pakistan, the third wave was taking off and countries were blocked to the Western world, so getting our guys out of there was a total nightmare. For our Canadian crew I cancelled flights five times, and there was rerouting.”

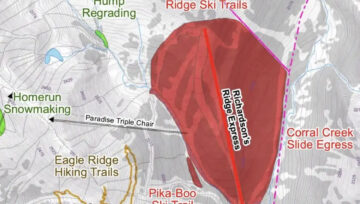

“The locations are essentially Switzerland, Canada, Peru and Pakistan and we have a bunch of others that started to happen but for one reason or another they were cancelled, due to the pandemic, or due to permitting, or due to the conditions. Nepal and India also hit the chopping block.”

It wasn’t just Covid making things complicated. “In Pakistan we were looking to fly drones in a heavily militarised country, so you have to involve the military, you have to involve the department of tourism, and it’s hard to know what to do,” Sangster continued. “There’s a lot of anxiety leading up to it, especially from my point as a producer, but we had some really good help along the way. In Pakistan they were thrilled with what we were doing because they want to show adventure tourism in a good light to the Western world. The military even donated helicopters, they put two sling loads of equipment up the glacier to where the guys were, free of charge, so those kind of miracles do happen.”

Pakistan in particular seemed to leave a truly indelible mark on the crew, and has the potential to surprise viewers, who may not associate the nation with snowy mountain ranges. But for director Eric Crosland, this the greatest place in the world to ski.

“Karakoram is the most beautiful mountain range in the world,” he declared. “It’s the most jaw dropping landscape you’ve ever seen. The mountains are like something out of a fairy tale book, they’re truly nature’s finest creation. But they come with really long approaches, it takes forever to get into them, you have to fly halfway around the world, drive for days and then walk for days, just to get to the bottom of them. By the time you leave your house it takes ten days to two weeks just to see the mountain from the bottom. The price of admission is time and safety to see these incredible place in the world, and it’s an honour and a privilege to be able to go to these places and hopefully we do them justice to what the actual beauty of them is.”

Even for the seasoned athletes who have travelled consistently around the world for years, this part of the job is still one of the most appealing aspects, and something that pushes them to keep going. But for Anthamatten it’s not just the scenery that inspires him, but those he is sharing the experiences with.

“Really it’s the people that you meet on those trips,” he said. “We have the wrong vision of Pakistan. It’s one of the most beautiful countries that you can travel to, you go to the mountains up there and they’re like ten times bigger than the alps. The people are super friendly and the food is great, the whole thing is amazing.”

“There’s nowhere else in the world that has mountains like Pakistan,” added Lavigne, joining in the chorus of praise for their experience shooting in Asia. “In a lot of places, like the Alps, you look at a mountain and it’s very jagged series of mountains and that’s the extent of it, whereas in Pakistan there’s layers upon layers of these Dr. Suess mountain scapes, and they really capture your imagination. There’s something about them that is hard to describe, because there are no other mountains like that.”

The beauty of the Pakistani landscape is evident within the film, but Heitz reserved special praise for those who inhabit this country, and how helpful and accommodating they were to the production.

“I came back with more memories from down the valley than up on the mountains,” he said. “People were naturally kind, they wanted to help. They’re just curious about how life was in our country, and they were showing us pictures of their families and inviting us to have some tea in their home.”

But then of course when dealing with this incredible footage gained from the experience shooting at the likes of Pakistan, the next step is showing off this wondrous aesthetic in a cinematic way, for this you require a talented editor to do the footage justice.

“There is a little bit pressure on me, because they go to such lengths to get these shots and some of these shots are absolutely incredible, and there’s no way you can’t not put those shots in the edit, while making sure you’re doing them justice in the edit by picking the best ones. But a lot of good stuff hits the floor, and that’s painful for everybody, especially when a shot has been so hard to get, but it’s just not working in the edit,” Symes said.

Symes spoke highly of his colleague, and director, Crosland, and how their long-standing friendship benefitted his process.

“Eric is great, we’ve established quite a good dynamic between director and editor over the years and this isn’t our first film together, but it is our longest one,” Symes said. “He puts a lot of trust in me. He’s a good friend as well so that makes it easy to have the honest conversations with each other about what you think is working and what isn’t working. But he’s got great creative ideas that I try and present back to him.”

Crosland was quick to repay the compliments for his editor, as the pair evidently share a strong professional relationship.

“Tim brought an incredible level of organisation to the storytelling,” he said. “He was just really disciplined storyteller, it’s really easy to let the music play and pick the best images, which is usually what happens in these ski edits. He was really dedicated to telling the story of what happened because reality is stranger than fiction and that takes a disciplined editor and a lot of organisation because the project was so huge with so much footage from so many expeditions, with so many interviews. He’s a true master of his craft.”

Comments