Morrison’s Hotel Wall

By Caleb Brown

The pilot dropped us off as close to our base camp as he could. We unloaded our equipment with the rotor blades still spinning overhead. Then, as he left us in a billow of cold smoke his voice came over the airwaves,

“Radio check from West Coast Heli.”

“Ya, this is Caleb from Camp Morrison, thanks for the lift!”

“No problem. -21 at the drop off, good luck out there…”

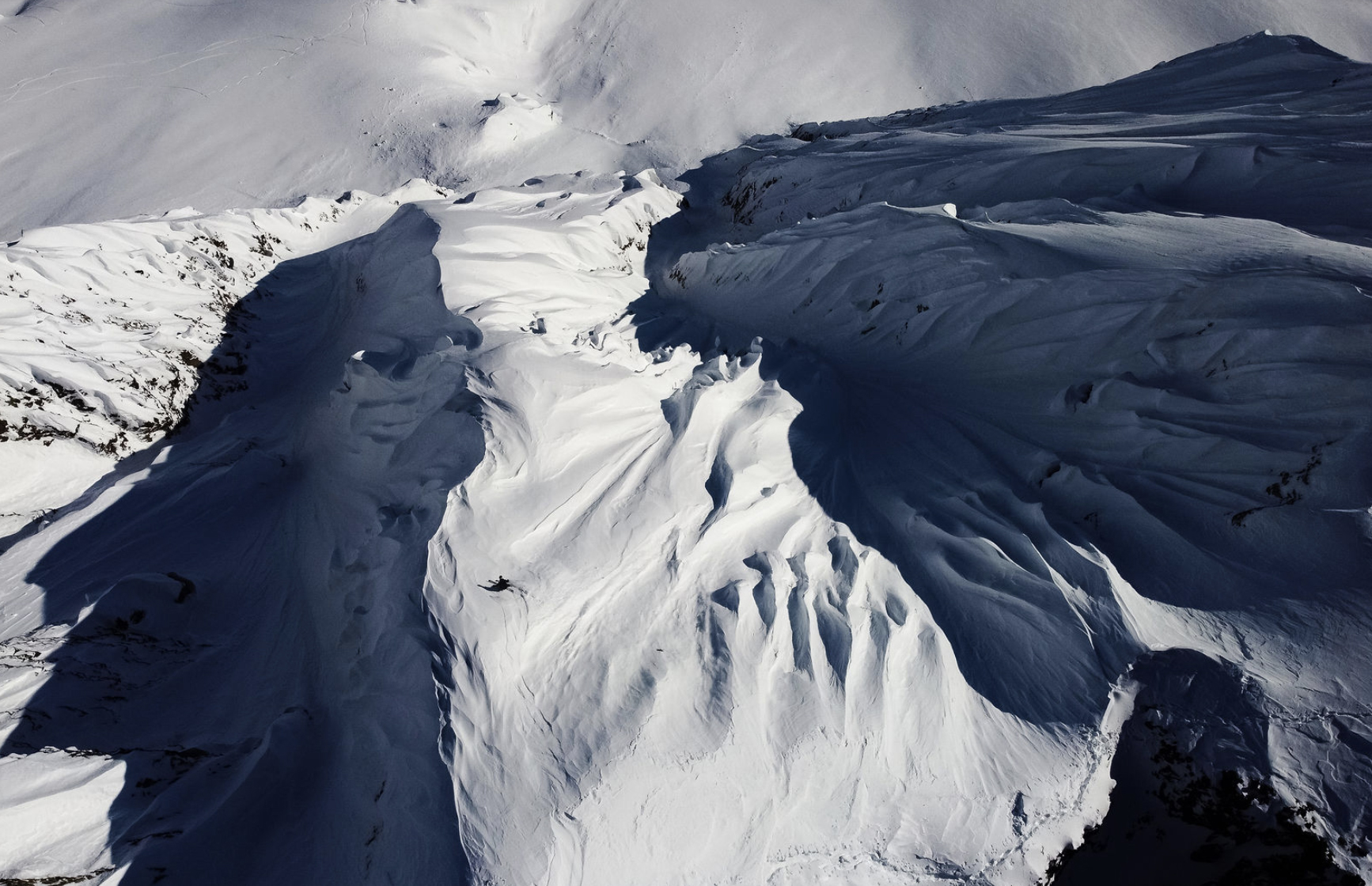

It was 5pm Saturday and there we were, beneath the face we travelled three days and 1,300km to get to. At first we let out cries of excitement, but as the noise of the chopper echoed less and less though the valley below we found ourselves staring at Morrison’s Hotel in an incredible silence. I couldn’t believe we even made it this far.

My journey started out in Fernie. I drove from there to meet Chuck Morin in Revelstoke. Chuck reached out to me about a month before and told me about this trip to the Central Coastals that his Japanese friend, Shika Ueki had planned with his photographer Tempei Takeuchi. Their plan had been in the works for months and Shika and Tempei needed a team. Chuck and Sheika met on a photo shoot, which, interestingly enough is how Chuck and I met. The team was then born only a short time before we were to meet in Bella Coola. So off we went, Chuck and myself in my truck a day behind Shika and Tempei.

The drive to Bella Coola was an adventure in its own. There is no cell service on the six hour stretch from Williams Lake, and the last two hours of the drive were unpaved. That road descends into the Coastal Range via Heckman Pass which is over 40km of steep, sharp and narrow turns with grades of up to 18%. There were a few spots where it was wide enough for only one vehicle to pass through. The road boarded huge cliffs that went beyond sight down to sea level and the corners and edges were unprotected by guard rails. Just making it down the pass felt like an achievement.

The team met as a group for the first time Friday afternoon in what felt like deserted streets of Bella Coola. The mountains were angry that day. Looking up to the peaks that stood over 2,500m above the valley was a north wind that was stripping everything in sight. Even in town the wind was fierce, so we hunkered down at the Cumbrian Inn and went over the gear and food that we had. We were prepared to spend up to seven days on the glacier, almost 50kms from civilization.

The plan was to fly out from Tweedsmuir Lodge the following morning but with -20 temps and over 100km/hr winds we seeked out information about what was happening in the high alpine.

Was the wind going to die down? When is it supposed to warm up?

Would there even be any soft snow left? What other zones could be worth hitting?

These were questions we asked a pilot at one of the nearby heliports. The wind was supposed to mellow out in the next day or two, followed by warmer temps. He gave us ideas for different zones because he was sure the snow had been stripped everywhere. After speaking with him, our mission of skiing Morrison’s Hotel seemed unattainable. We agreed that we needed a second opinion so we drove up the valley to Tweedsmuir Lodge.

The guides from Bella Coola Heli at Tweedsmuir were confident that The Hotel Wall might be some of the only good skiing in their tenure. Nothing was certain, it was still a roll-of-the-dice, but we agreed that is how it goes in the mountains. The four of us huddled together and went over our options and decided to stick with our original plan. It was back on. We left the lodge with a simultaneous sigh of relief. We were flying out the next morning.

On our first load to the trucks on Saturday we discovered Shika’s truck had a flat tire. That was the first hurdle. We battled through it in the crazy winds, then started back towards Tweedsmuir Lodge. We made it only one kilometer out of town and the wind was testing the strength of the timber beside the road and I said to Chuck,

“I feel like we’re going to be hit by a tree…”

As we came around the next corner there were three trees down and a two car collision in front of us. These were all signs that we could not ignore.

Are we on the right track? Or is this just a test?

After spending the morning killing time in the local cafe drinking coffee and tea amongst the locals we weren’t sure if we should fly that afternoon, but we agreed that we should go to the lodge and get a feel from there. When we arrived the pilot was ready. We meant to have a team meeting and discuss the wind and temperature situation (it was supposed to be -25 in the alpine that night) but all of a sudden we were loading up the heli. If there was going to be any wind up there we were flying into a miserable situation.

Once dropped off, we stood looking in silence at the line named after Seth Morrison and felt extremely grateful that there were only moderate winds. The cold still nipped at any skin that was showing and the sun was setting, it was time for action.

From the heli drop-off we scoped a site, then made teams of two and tied our gear together to drag downhill to our base camp. Once everything was set up we enjoyed the first of many pastel sunsets and stared some more at Morrison’s Hotel Wall, even at dusk it was glowing.

Tomorrow was our inspection day; our goal was to set the skin track and the boot pack to the ridge. Dig a pit, and study the snowpack. Then find the entrance to Morrison. As we fell asleep that night none of us knew if the snow on the face was skiable. The next day would reveal everything.

We woke in the cold, but the sun invited us out of our tents. Morrison bid us good morning and we started the climb. Once we got closer, it’s true size came to life. From halfway to the peak our camp was almost lost in the vastness, the only way I could see it was by following our skin track that led from it. It was the only inconsistency in the entire landscape.

From the highest part of the face it was a short down-climb to the main entrance. We were only able to see about eight meters down the start of the spine, then it dropped off into the abyss. The snow was firm at the top, and we assumed it was similar through the crux and into the main line. We all just looked, and hardly spoke until we wrapped around, back down the bootpack to the bottom to have a look from below.

Back at camp our group discussion went something like this:

“It goes…”

“Even if the snow isn’t great, it’ll be skiable…”

“But if the snow is soft, sluff management is going to be key…”

“And keep in mind, this is not a line to flash, we need to ski carefully and conservatively. We are a long way from help.”

The voice of a guide we spoke to a few days prior echoed in our minds, “You guys are going for Morrison? You know a guy died there a few years back…that’s why film crews don’t ski it anymore. Head injuries are brutal. Lots of blood. Watch out for your sluff.”

That night we studied photos that Tempei had taken from the flight in. Those gave me confidence as I analyzed them in my tent. I fell asleep easily but woke in the middle of the night with a pinch of fear in my gut, and by morning I was terrified.

I forced myself out of my tent into the darkness and rammed my feet into my frozen boots. As we headed up our skin track the half moon was playing hide-and-seek behind Morrison’s Hotel. Tempei watched eagerly from his photo perch as we disappeared over the ridge.

“You guys are ahead of schedule, which is good because the sun is warming everything quickly. The sooner you drop in the better.”

“Copy that,” said Chuck. “We are nearing the peak. We will let you know when we are ready.”

Minutes later Shika was poised, standing at the entrance. This was the moment he had been waiting for. The moment he had dreamed up months ago and made a reality. I felt blessed to be there with him.

He dropped in with purpose, without fear. Then he was gone. Chuck and I waited minutes that lasted an eternity until he came flying out the bottom. Cheers came over the radio from Tempei.

“The first few turns are firm,” Shika said, we could feel the excitement in his voice, “then the rest is pow! Just watch out for your sluff, there’s a lot of it and it is strong!”

Chuck and I looked at each other, eyes wide. It was on.

Chuck was next. He too disappeared forever. Then, there he was, a spec in the distance below. I felt jealous of those two. They were done. Embracing each other at the bottom, and here I was, alone at the top. Without any more time to think Tempei’s voice came over the radio.

“Whenever you’re ready, Caleb.” I clamped my boots.

“Dropping in 3, 2, 1…”

Shika was right, the top turns were firm but as the spine rolled over and began to creep towards 50 degrees the snow quality increased. This line was extremely exposed. To the left and right were cliffs into each opposing chute, and way down below were close out rock faces that we had to maneuver around. The entire run was a no-fall-zone.

As I made my way off the spine onto the hanging snowfield I couldn’t believe the further I went, the steeper it was. The technical part was now over. Linking turns and managing the snow around me I headed for the exit, slashing one final turn on the last spine above the cliffs. My legs begged for rest as I raced my sluff over the bergschrund.

With a line like that it is hard to say which is the best part. Is it the anticipation of standing at the top? Being smack dab in the belly of the beast? Or is it the last turns out of the bottom? Each segment, including the climb is what makes this type of skiing so special.

Camp vibes were exceptionally high that night. We are officially the first self-propelled team to summit and ski Morrison’s Hotel. Only a day later, it felt like a distant memory, almost dream-like, but a memory that will never be forgotten. Imprinted in us like our tracks on the wall.

Comments