Powder Skier: Erik Boomer

By Jon Turk

It was the summer of 2010 and Tyler Bradt, my wife Nina, and I were sitting in a coffee shop in Hood River, Oregon, sipping lattes and dueling laptops, to plan our upcoming circumnavigation of Ellesmere Island. Every bit of data made the journey sound ever more grim and difficult: Moving ice, arctic cold, tempestuous oceans, and marauding polar bears. Finally, Tyler, who is always so buoyant and confident, shook his head: “We need more firepower. I’m going to call Boomer.” And without waiting for any response, he picked up his phone.

I didn’t say anything, but my first thought was, “Oh, Boy, what kind of guy would attach a nom de guerre like “Boomer” to himself?” It turned out that Boomer was off kayaking the Stikine Canyon, one of the most difficult and committing whitewater runs in the world, but he was due to return to Hood River, Oregon, soon. Nina and I hung out with Tyler for a day or so, until we got word that Boomer was on his way, driving straight through the night, from west central British Columbia, to connect up with us. We returned to the coffee shop, caught up on emails, and soon enough, a beat up, rusted, generic white car pulled up. The first thing I noticed, aside from the fender that was about to fall off, was that the back seat was packed with everything imaginable, a clear sign that this was not only a means of transportation, it was also home. Every other kayaker I’ve ever known has a roof rack to transport his boat. But, Boomer had sidestepped that purchase by pounding in the roof itself with a heavy hammer, to create an indent, and then he simply nestled the kayak into the custom-fitted depression.

A burly guy of medium height stepped out and walked across the street with easy athletic grace, blinking in the sunlight, appearing a little ragged after driving all night. He had a thick mop of strawberry-blond Scandinavian hair, the kind that changes color easily with sun and wind, and disarmingly blue eyes. Although he seemed friendly enough, I thought that if, in another lifetime, he charged to shore from a Viking longboat, splashing through the surf with a horned helmet and a battle-axe, I would run for the hills.

He greeted Tyler then offered his hand to me with a warm, understated, boyish smile, “Erik Boomer, pleased to meet you.”

“Oh shit,” I thought. “Boomer is his real name, the name his mother and father gave him, not some contrived nickname. I’ve already underestimated this guy.”

And indeed I had. We went inside and ordered more coffee. Tyler outlined our project and I watched Boomer’s face. Boomer nodded casually as if we were discussing a Class III trade run of a local river, “Sure, I’m in.”

The rest is history. Tyler broke his back dropping a waterfall and Boomer and I set out alone – together — to succeed in the Ellesmere Expedition, which Arctic historian Jerry Kobalenko called “One of the last great undone feats of Arctic exploration.”

When we parted at the end of that journey, I was in a medi-vac aircraft, dying, doped up on morphine, and Boomer was charging off like the Eveready Bunny, to meet his Arctic-explorer girlfriend, Sarah McNair-Landry, after spending 104 days in a smelly tent with me.

Well I didn’t die.

After that expedition, we hung out together a few times to do some shows and collect some awards, but we never quite caught up to play. Then, just a few days ago, I got an email from Sarah, announcing that they were coming up to visit, along with a friend named Willi, to hit the Fernie backcountry with Nina and me.

With a little bit of fame and some crafty promotion, coupled to the Ellesmere thing and an ever expanding resume of cutting edge kayak drops, Boomer has moved up in the world. He still lives in his car, and it’s still white, but he has a van now, the fenders are securely attached, and the roof is nicely concave, just like when it rolled off the assembly line. As Boomer proudly told me, “It’s registered, it’s home, it starts when I turn the key, and stops when I put on the brake.”

We had an unforgettable week of stable, creamy, faultless powder in the Fernie backcountry. On day four, we were boot-packing down a narrow chute, in a blowing snowstorm, to access one of my favorite runs in the whole world. The chute is about 50 degrees, and people have skied it, but not now, with only a two-meter snowpack and a fangle-tooth rock grinning up at you from 2/3 of the way down.

When it was my turn to descend, I felt a bit sketched, trying to kick steps into frozen dirt and exposed rock. Then a thought occurred to me and I looked up at Boomer’s smiling face at the top of the chute, “You kayak stuff this steep all the time, don’t you.”

He smiled, a smile I know so well by now, “Some of the time.”

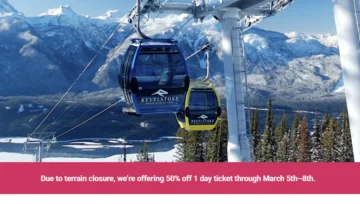

The next day, riding the chair at Fernie Alpine Resort, I asked Boomer if he was going to ratchet up the ante in skiing, as he had in kayaking, and drop big faces with the pros. He shook his head, “No, I just want to keep my feet on the ground and ski beautiful lines with my friends.” But when I took out my camera a few minutes later, Boomer couldn’t help being Boomer, launching as much air as he possibly could.

Comments